For #SlashedandMashed Release Week, I’m sharing some book extras. Today I thought I’d post an excerpt from the lead story in the collection “Theseus and the Minotaur.”

I wrote “Theseus and the Minotaur” almost two years ago when I was prepping to start my Patreon page and wanted to front-load some of the work providing content for patrons. I love Greek mythology, so a natural place for me to start was re-imagining classic myths and giving them a queer spin.

On re-familiarizing myself with the source material, a couple of things stood out to me and got my creative gears spinning. First, like most Greek heroes, Theseus was really young when he set off on his adventures. Greek writers and historians were pretty stingy in the area of development of character, and of course, they didn’t think about human development in the same way we do. But I was struck by the opportunity to flesh out Theseus as a young adult, just entering manhood as was said, which might have meant he was 18 years old or younger.

Then, even more so, I was drawn to redeem the tragic beast character the Minotaur, who like so many Greek monsters (e.g. Medusa, the Cyclops) had a cruel and haunting history and was spared no kindness, no humanity in the source material.

Last, I was struck by the relationship between Theseus and Ariadne. They’re both described as idealized beauties, and some versions of the story portray their relationship as romantic. But it’s not told as a triumphant romance like Perseus and Andromeda or a tragic romance like Jason and Medea. The myth writers were pretty wishy-washy about Theseus and Ariadne. One version has Theseus dropping Ariadne off at an island on his way back from Greece, for example, and in any event, it’s not described as a lasting relationship. Ariadne was linked to the god Dionysus by storytellers of the time for example. That got me thinking about who really captured Theseus’s fascination on his trip to Crete.

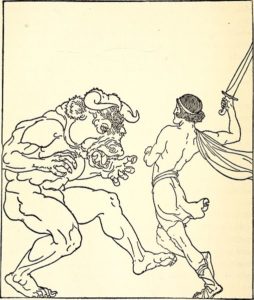

Anyway, here’s a short excerpt from my story when Theseus first meets the Minotaur in his quest to kill the monster of the labyrinth. My husband drew this sketch to go along with the story.

Slashed and Mashed

Andrew J. Peters © 2019

All Rights Reserved

THESEUS HELD HIMSELF silent for a moment. The dimensions of the chamber surely signified something, whether a pit lay in its center for him to trip into, or his trail had led him to the heart of the labyrinth. Casting his gaze here and there, he regretted he had so few markers with which to judge. But, oh yes, that looked like straw scattered on the ground, such as could make a kind of bedding. And, oh yes, a familiar scent traveled to his nostrils, which spoke of habitation, as a house held on to the peculiar smell of its occupants, bare feet upon the floorboards, odors seeped into leftover clothes and bedsheets. This scent he would describe as hide and the earthy smell of a man freshly woken from a night’s sleep. He stood on guard, thinking about how quickly he could wield his sword.

Now, faint breaths arose from the sightless depths of the chamber. Not slumbering breaths but more carefully measured, like a man (or creature?) concealing itself. Switching out the bobbin for his sword, he staggered forward a few paces, pointing his torch ahead of him.

“Show yourself and let us end this game.”

A daring vow that overplayed his true grit. For when a shadow rose from the floor, towering a head taller than he, and a murky silhouette lurched toward him, the prince could only hold his ground, transfixed by the adversary he had summoned.

Twisted horns sprouted from an impossibly broad and jutting forehead. The shoulder span and thickly muscled torso of a demigod. The creature was entirely bare from its bulging chest to its manhood to its thick, crushing thighs. Bowlegged by its anatomy, it walked upright with powerful strides.

“You’ve come to smite me?”

A further terror. It spoke. Yet in a voice more human than Theseus would have imagined. Deep and virile, as befitted its proportions. Theseus stared back at its black-eyed, challenging gaze. He could not produce a word.

The Minotaur curled its mouth. “If you are such an adventurer, I should like to know your name before you try your sword against me.”

Theseus threw back a foot, bent his knees in a defensive stance, and wielded his sword, one-handed at his shoulder. “I am Theseus of Attica. Son of Aegeus. Prince of Athens. Enemy of Crete.”

The Minotaur cocked its head slightly. A strange gesture for a man-eating monster. Though its horns, its size, its physicality spoke of dominance and destruction, it did not seem to be tensed for battle.

“What is Attica?” it said.

“A land far from here. Across the Aegean Sea.” Theseus elaborated no further. Curious as it was that the man-bull wished to talk, he had not come for conversation. His gaze passed over the leather collar around the creature’s neck, and he breathed courage into

his lungs.

“Your father declared war on us. As did your god. I have come to end it.”

He rushed at the monster with his blade outstretched, ready to hack. For a moment, he thought he had caught his enemy off guard. Then, in a blur, the Minotaur struck out and caught his sword arm in its hand with an impossible strength.

Theseus fought to free himself, and then the hilt of his blade slipped from his hand, and his only weapon clanged on the floor behind him. The monster held him in an iron grip. He twisted the prince’s arm and shoved him back. Theseus barely managed to stay on his two legs and not drop his torch.

No sooner had he raised his eyes than the creature came at him again. Now, he looked distinctly peeved. (And the Minotaur was no longer “it” in the prince’s head. Theseus had expected to fight a creature more beast than man. He found instead an adversary with human intelligence, the capacity to speak, composed of human flesh but for twisted horns and hooves. “It” was “he.”)

“What do you know of my father? What do you know of my god?”

Theseus pivoted around, anticipating a strike, unable to take his eyes off his challenger in favor of searching for his blade, which he desperately needed.

The Minotaur rounded him. “Speak. You’ve come a long way to tell me about my origins. Would you stop now?”

“Your stepfather, I meant,” Theseus said. “The King. He is my enemy. As are you.”

The Minotaur snorted. “Yes, stepfather. My warden. He is no father to me. Would a father keep his son in a cold, dark crypt, Prince Theseus?”

Theseus supposed it would not be so. Judging the space and the creature’s reach, he could see no opening for an attack—with only his bare hands? A spree to escape the creature was slightly more plausible.

“I will have justice,” Theseus snarled. “Your country has terrorized my people and driven us to starvation.”

The Minotaur’s eyes passed over the prince from foot to head. “You do not look so badly used, nor fed.”

“I have been chosen as my country’s champion.” Gods, his voice had cracked like a petulant boy. Theseus tried to shake it off. “Your father, I mean Minos, is a child murderer. If I do not succeed, Athens must send him fourteen children to enter the labyrinth.”

The beast took that in for a moment. “Children? Well, Minos is a master of cruelty. I do not answer for King Minos’s nature or his crimes.”

Theseus’s eyes flared. His impartial acquittal of the matter was vexing, seemed mocking. “Are you not the lord of this den?” Theseus waved his torch arm around. “Is this not your house? Your hunting ground?”

A mirthless smile came back at him. It was gone as quickly as it had appeared. Though it would be too much to say the prince regretted his words, he was in an instant aware he had unleashed a fury—to which he possessed no equal reprisal—from an opponent who stood much taller and broader than he, and had pointed horns.

The Minotaur overtook the space between them and railed, “Yes, I am your beast. Your Minotaur. Tremble before me as men have done since the day of my birth. Dread monster. Man-eater, they call me. Hated by all who behold my horns. Banished to this underworld lest women faint and children cry from the sight of me. Scourge of the earth, so foul it entraps men to dine on their bones. Are you not afraid, Prince Theseus?”

# # #

If that whets your appetite for more of the story, you can pick up the anthology here.