Three posts in as many days? How do I explain. I think it’s part neurotic overcompensation (I won’t be posting again until the week of August 14th) and part pre-Writers Retreat mania. Anyway, I’ve been working on this review for a little over a week, it’s done, so I’m posting it.

Trying to catch up on recent ancient world fantasy, I picked up David Gemmel’s Lord of the Silver Bow. It’s the first book in Gemmell’s Troy trilogy, which reimagines the famed conflict between Mykene Greece and Troy, this time from the Trojans’ perspective. A British author, Gemmell died in 2006.

Who am I to critique Gemmell, one of the most prolific and popular writers of heroic fantasy? My study of the genre is growing, but still spotty, and I have two unpublished historical fantasy manuscripts to my name. So take this review as the perspective of one writer, one reader with an interest in the time period, and the mythology, and a preference for great characters and stories that illuminate our state of being, triumphant and horrifying as it is.

Lord of the Silver Bow casts Aeneas—Gemmell calls him by his childhood name Helikaon—as a respected military hero, and a reluctant politician. He abdicated his claim to the kingdom of Dardania, a strategic ally of Troy, because he blamed his tyrannical father for his mother’s suicide.

The central story concerns how Helikaon will find his way in a brutal world that’s undergoing rapid political changes, and switched alliances, including those that guide who he can or cannot marry. When he falls in love with his Trojan cousin Hektor’s bride-to-be Andromache, he’s caught in a familiar bind: will he follow his heart or follow his duty?

Adding to the tension, Helikaon is being targeted for assassination by a multi-national pact to avenge the death of a popular Greek war hero.

I found that the story shone brightest when portraying the complexity of human nature. Warriors commit merciless acts, yet they are fiercely protective, even tender toward their family and comrades.

One chapter concerns a mercenary who murdered Helikaon’s half-brother and raped his stepmother. Hard to portray a rapist in a textured way, but I feel that Gemmell succeeds by telling the story from the mercenary’s point-of-view. There’s no apology or circumspection, but I thought it was a realistic portrayal of a ruthless military lifestyle in which the choices are to kill or be killed; and the men therein guard their place, and loved ones, by a vicious cycle of ever-increasing violence.

It’s the character contradictions that make for the most interesting reading here. Bound by a code of honor to refrain from violence as a guest at a foreign feast, Argurios, a Mykene, a natural enemy of Helikaon, slays a pair of his countrymen when they try to assassinate the prince. A master assassin proudly reflects on having made his way by killing men, but per a priest’s advice, he will only carry out his vocation from Spring to Autumn so as not to displease the god of the Underworld. Beliefs around religion, ethics, morality are evocative of an ancient time, yet the questions and struggles resonate well today. Is there ever honor in violence? Can a man who commits monstrous acts be redeemed?

Less successful for me was the narrative structure. The story changes point of view every single chapter, with over two dozen character perspectives represented, and many of them are minor characters rarely or never to be heard from again. Each chapter feels satisfyingly complete, a nice short story in itself. But early on, I found myself wondering: who and what is this story about? Ostensibly, it’s Helikaon’s journey, but he disappears for such lengths of time, I didn’t fully engage with him.

The length is also daunting for a story that only lasts a week or so: nearly 500 pages! There were times I slugged through it rather than enjoyed it.

Another weak spot was the romance. Part of the problem relates to the above, not enough focus on the couple we’re supposed to care about: Helikaon and Andromache. But I didn’t trust that the author had it in him to create a compelling love story anyway. There’s a cliched love-at-first-sight meeting (forgivable if there’s an intriguing follow up), but it was kind of like trying to root on the two most popular kids in school. Helikaon and Andromache are treated so generously, I didn’t really care if they ended up together. Slightly more compelling is the counterpart love story between the hardened, exiled Mykene warrior Argurios, and always-the-bridesmaid-never-the-bride princess Laodike.

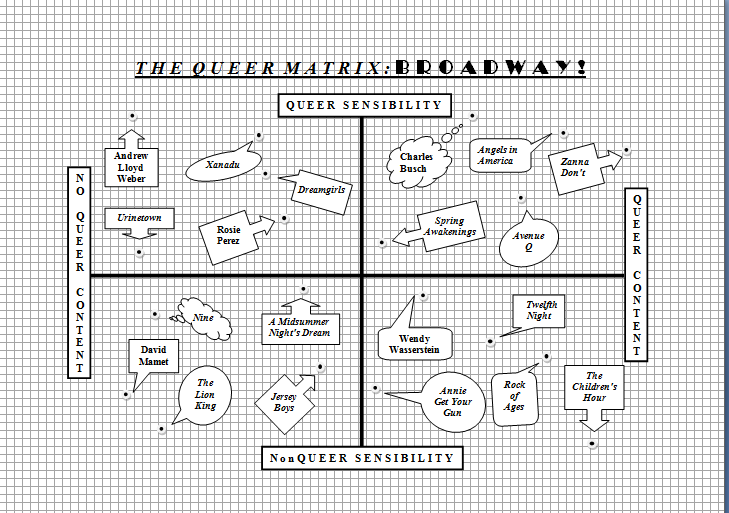

But most regrettable was the portrayal of Andromache’s bisexuality. It’s a facet of the story that appears to exist solely to titillate non-gay readers. There’s no depth to Andromache’s (supposed) affair with another woman from her wild lesbian-segregated past, and meeting Helikaon, of course, “straightens” her out anyway.

So, I give Lord of the Silver Bow three stars or maybe a B-. I don’t know that I will read more in the series. On one hand, there’s terrific rendering of the ancient world setting and sensibility. But there’s room for improvement in character development and the complexity of romantic themes.