If you saw my earlier post this month, my New Year’s resolution is to share more of my work with my website visitors. I also started a project to create short stories based on classical mythology, which might some day parlay into a collection. My first piece is ready to share with you.

I’ve always loved the story of Theseus and the Minotaur, which is credited to second century B.C.E. historian Apollodorus of Athens in Edith Hamilton’s Mythology, and Plutarch and Ovid elsewhere. It’s so imaginative, and it’s been an enduring inspiration source for artwork, fantasy, and gaming. I remember walking through Tuileries Garden in Paris and stopping in my tracks when I discovered a nineteenth century neo-classical statue of the two, and naturally I had to take some photos of it. Years before that trip, I confess I was briefly addicted to the RPG Neverwinter Nights, which includes a labyrinth filled with stalking minotaurs. The story is so irresistible, I suspect it figured into just about every Greek mythology-based TV series, from Hercules to Xena to Olympus. I know it was in an episode of the BBC’s short-lived Atlantis series. Given that wide access point, I thought it was a great place to start with my project.

Here, I hoped to give more dimension to the characters, and some spin. I had always thought of Theseus as a pretty dull, do-gooder, the archetypical, epic hero like Jason and Perseus, admirable but not so relatable to the reader. He certainly was depicted that way in the big screen bomb Immortals. But when I re-read some of the classical myths about him to reorient myself, I found a hint of personality. Theseus used his brains as well as his gods-given physical abilities. I wanted to expand on that, in addition to how he might have truly felt about his heroic quests as well as his unusual origins.

I had no idea it would turn into such a long, short story. It’s really just five scenes, but I found myself digging pretty deep with each of them. I was entranced by how Theseus might have experienced his trip to Crete, and I hope you will be too. So I’m going to release the story here in three, fairly long installments. The entire story is a little over 16,000 words.

Now, without further ado, here is Theseus and the Minotaur, Part One.

Illustration by Willy Pogany, from “The Golden Fleece and the Heroes who Lived Before Achilles” by Padraic Collum; retrieved from Wikipedia Commons

THE GREAT hall of the king’s palace was vast enough to house a fleet of double-sailed galleys, and its grey, fluted columns, as thick as ancient oaks, seemed to tower impossibly beyond a man’s ken. Prince Theseus had been told, he had been warned of the grandeur of the Cretans, how it was said they were so vain, they forged houses to rival the palace of Mount Olympus. Yet to see was to believe. For a spell, the sight of the great hall stole the breath from his lungs and made his feet drag to a stagger. Should not he, a mere mortal, prostrate himself on his knees in a place of such divine might, such miraculous invention? It felt as though he had entered the mouth of a giant who could swallow the world.

No, he reminded himself: this was all pretend, a trick to frighten him and his countrymen, though he only half-believed that. Silenos, an aged tutor who Theseus’s father had hired to teach him all things befitting a young man of the learned class, had cautioned him not to trust his eyes, that these pirates of Crete used their riches to build a city of illusions so any navy that endeavored to alight at its shores would be hopelessly confounded and turn back to sea in terror.

Theseus forced a dry swallow down his throat and retook his steps to keep pace with the soldiers who escorted his party into the hall. He had brought two of his father’s naval captains to accompany him, and the king had sent three men for each one of them to meet them at the beach where they had rowed ashore. From there, they had been conveyed up a steep, zigzagging roadway to the palace. The armored team looked like an executioner’s brigade rather than a diplomatic corps. They were hard-faced warriors with spears and clad in bronze-plated aprons and fringed, blood red kilts.

He tried to look beyond many wonders and train his gaze on the distant dais where the king and his court awaited him. Yet curiosity bit at Theseus. Oil-burning chandeliers seemed to hover in the air, hung from chains girded to a sightless ceiling. No terraces had been built to bring in daylight, nor doorways to other precincts of the statehouse, unless they were hidden. The walls shimmered with a metallic reflection of the room’s massive columns, affecting the appearance that the hall went on to infinity. The diamond-patterned carpet on which he trod was one continuous design stretching from the vaulted doorway where he had entered all the way to the other end. Such a carpet was surely large enough to cover the floors of every house in Athens!

As he neared the stately dais, he beheld the king’s high-backed throne of ebony, and he glimpsed very briefly the man himself along with the shadowy members of his court. Theseus lowered his gaze to disguise his impressions. He supposed it also counted as a gesture of respect. He followed the soldiers into a lake of light which glowed from thick-trunked braziers on either side of the hall’s carpeted, shallow stage.

Their steps ended some ten paces in front of the room’s dignitaries, including of course the king himself. The armored men knelt on one knee, drummed down the handles of their spears on the floor, and bowed their helmet-capped heads as one company.

That left Theseus and his consorts standing and wondering what to do with themselves for a worrisome moment. To kneel to the king was to surrender Athens’ sovereignty, and that had not been his father’s bargain. Though his princely leather cuirass and his laurel crown felt countrified, almost absurd while he stood before the king, Theseus did not break. He glanced to each of his companions so they would know they should neither kneel nor bow.

Righteousness grew inside Theseus, arisen from the unsurpassed conviction of a youth of eighteen years whose dealings in the world thus far had not acquainted him with indignity, the shock of being cut down to size. As an infant, he had been sent to live in his mother’s village, which was countries apart from the political fray and urban discontents of Athens. This, no excess of fatherly protection, but a testament to his father’s severity, later spoken of in the ennobling light of superstition, an augury of the night sky or some such. Aegeus had decreed: if his son was worthy to succeed him, he must earn the right on his own terms.

For most of his life, Theseus had not known his father. He had not even known of his paternity, though he had lived quite well as a handsome, rugged lad among country folk who required no more than that to smile upon him, fetch him apples, give him a rustle on the head when he passed by, a proud acknowledgement he was one of their own. Then came his mother’s confession, and his storied trek to present himself at his father’s court, which he had made on foot across Arcadia, an ungoverned, forested land that had been said to be rampant with all manner of bandits, ogres and mythical beasts. In Athens, he had been a newcomer, an adventurer, and a fawn-haired swain, all of which had earned him magnanimous gossip. Men made way for him, and women smiled and idled when he passed by.

Naturally, young Theseus was aware of none of this as a favored flower does not question why it thrives in sunlight, has a gardener always at the ready for its succor, while others of its kind turn spiny and dull from negligence. Or, it should be said, a glimpse of his place in the world, past and present, was only just then taking form while he stood in King Minos’s great hall. He did not like how it made him feel.

He shook off the sinking sensation. He would be bold, for he alone stood for Athens in this house of tyranny. These foreigners had butchered his countrymen, raped their women, taken their daughters and sons as slaves, and burned their fields. He alone would end the war, and in truth it did not matter if he returned to Athens on a white-sailed galley to herald a hero’s return or if a black-sailed ship should come back to his father, signaling that Crete had been his final resting place. So had he decided. He looked to King Minos to begin.

The Cretan king returned his gaze, appraising, taunting, and then he perched in his seat and craned his neck to see beyond the prince, to turn a querulous eye at the head men of his squadron. “Where is Athens’ tribute?” he spoke. He looked to be no more advanced in years than the prince’s father, a sturdy, dispassionate age. The similarity wore through at that. The king’s dark brown beards were plaited and shone with oil, and he wore a miter banded with red-gold. He was clad in raiment of deep cerulean dye and a draped, red stole, all adorned with fine embroidery and fringe. Theseus had never seen a man so richly clothed and groomed. His father, the wealthiest man in all of Attica, had only a sheep’s fleece and a laurel crown to say he was king.

“King Aegeus has sent me, his son, Theseus of Attica, to answer your request,” Theseus spoke.

Minos pursed his lips, sucked his teeth. “I asked for children.”

Such had been the compact signed by Theseus’s father to end the war: seven boys and seven girls surrendered to Minos in return for nine years of peace, during which the Cretan king had pledged he would call back his warships.

It was a war begun while Theseus still lived with his mother in the countryside, years before his mother had taken him to an unfarmed field outside the village and shown him his father’s buried sword, from which he came to know his origins. Theseus had only arrived in Athens one season past and been apprised of the history. This heartless war borne from a tragic misunderstanding.

Two years ago, Minos had sent his son Androgeus to Athens on a friendly embassy, and while Theseus’s father had taken the youth on a hunt to see somewhat of his country’s pastimes, Androgeus had been thrown from his horse, and landed headfirst on a rock. No physician nor priest could restore him. His spark of life had been extinguished all at once.

Aegeus had returned the prince’s body to Crete with all due sacraments and compunctions. His priests had washed Androgeus to prepare him for his passage to the afterworld, and the king had sent him across the sea on a bier of sacred cypress, ferried on his finest ship, oared by his best sailors, and with a bounty of funereal offerings, gold and silver, which was many times more than his kingdom could afford. Yet Minos declared treachery and turned fire and fury against Athens.

Three seasons the war had raged, and after a decisive battle on the Saronic Gulf, Minos had claimed that vital sea passage and installed a naval blockade, robbing Athens of her trade routes, slowly starving her. Aegeus had appealed to the Cretan king for an armistice. An emissary from Crete had returned with the tyrant’s reply: fourteen innocent lives for the price of his son. This, after Crete had already extracted the lives of hundreds of fighting men in payment for his one son, whose death could only be blamed on the cruel, mysterious Fates. Would Minos continue his assault until every man and woman of Attica had been exterminated? Who could stop an army empowered by the God of the Sea?

Aegeus had decided he had no choice but to agree to the king’s terms, and his council, one and all, had supported him. The Athenian navy was no match for the foreigners by the numbers nor by the craftsmanship of their vessels. The Cretans flung barrels of fire from catapults. Their triremes were faster and their battering rams were more potent, carving apart a galley on a single run. The Athenian fleet had dwindled to a dozen vessels. Their forests were stripped of lumber, and even if they had the resources, their ship builders could not assemble new warships fast enough. Food shortages had depleted their force of able-bodied men to defend the city. Without a reprieve from war, the next attack on Athens would be the last.

But after the lottery had been held, and weeping fathers from all parts of the country brought their sons and daughters to the naval pier where they would be ferried across the sea, Theseus could not bear it. He looked upon the children, who were as stunned as lambs without their mothers, and he had wept for them, and wept for his country, and wept for the shame of being part of this abomination.

Then, in a rush of rage, Theseus had attacked the sailors who would lead the children to the ship. He had come to know them as friends, yet all he saw were blank-faced monsters. By grace, he had only had his fists, and no man had raised a blade to stop him. Theseus had shoved, struck, and menaced perhaps a dozen before they overtook him and held him fast by his neck and arms. A terrible blackness ate up his vision, and inspirited with a daemon’s strength, Theseus had thrown off his captors. He turned his fury at his father who stood at the landside end of the quay with his councilors.

Theseus had shouted at them vicious oaths he had not known were in his vocabulary, and he spat at them. Did they not know what they were doing was an offense to the goddess? It was a betrayal of every free man of Attica. His throat was scorched from shouting, his voice hoarse, and he fell to his knees, dropping his bonnet, weeping and pulling at his thick, curled hair.

He looked up at his father. “Please, send me.”

Now Theseus faced King Minos intrepidly. “I have been chosen to stand for the children. I have only eighteen years, turned just this past season, and I am my father’s only son. I will face your contest.” He realized only then he had forgotten the honorifics, which Silenos had taught him. In Athens, men spoke to their king as freely as they spoke to their own fathers, and for the prince, that person was one and the same. No matter. It was never a mistake to put one’s enemy off balance. He could see the king was alarmed, as though his lack of manners had been intentional.

Theseus continued, “Accordingly, should I fail, you shall grant Athens nine years without hostility so that my country may grieve my death. And, should I succeed, no man of Crete shall sail upon Athens’ seas within the same period of time. This has been sworn to in your covenant with my father. This is what I have come to do.”

The hall fell as silent as a winter forest. Only the king’s courtiers shifted a bit like the stiff branches of February trees. They were wondering no doubt what reckoning the king would make of this prince, offering himself in defiance of the terms of the compact. It had to make for a tempting proposal. How better for Minos to show off his might and humiliate Aegeus? He could say he had coerced the great king of Athens to sacrifice his beloved, only son, and kings from around the world would rush to pay him tribute lest he demand the same of them. Theseus needed it to be so. Nothing from the man’s history suggested he could be persuaded by mercy. It was said that when he had sacked the wealthy trade-city of Khirokitia on Cyprus, he had ordered his sailors to rape every one of the Cypriot king’s eleven daughters, some as young as five, and then to bind them to the hull of their ship so the girls would drown on the voyage back to Crete.

Theseus felt the cruel king’s eyes upon him. He scrutinized the sword holstered from the prince’s belt, the broadness of his shoulders, the musculature of his arms and legs, which showed outside his short-sleeved, thigh-length chiton. The prince was still a thin-hipped youth, though his limbs had hardened from martial training. The whiskers of his cheeks and chin remained downy, and his face had not yet fully shed the glow, the plumpness of boyhood.

“You will face my stepson in his lair?” Minos spoke, a glint of humor in his eyes. “With only a blade to defend yourself?”

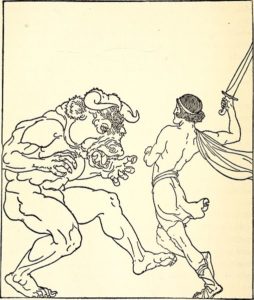

The prince nodded. The Minotaur. Sired by the snow-white bull that pulled the god Poseidon’s chariot, and borne from the king’s mad wife Pasiphae. The legend held that Minos kept the creature in a subterranean labyrinth, and it only fed on the flesh of men.

Theseus noticed a strange man who stood aside the king’s throne taking account of him. The gruesome fellow was nearly naked and glistening with oils. His grey skin hung from the bone and was creased with age. He wore a feathered headdress, a swath of fabric as a pagne, and a heavy necklace of horns draped on his flat chest in tribute to the fearsome god he worshipped: Poseidon, Roiler of the Sea.

On the other side of the king was a woman dressed in a layered gown of widow black, and with a veil covering her face. The king’s queen, Theseus guessed. Still in mourning for the death of Androgeus.

He turned to a fair girl on the stage who stood beside the queen. She had vigorous locks of black hair heaped upon her head, and her face had been painted in ochre and rouge in an Asiatic style. Her clothes were colorful and immaculate, entirely foreign to the young prince. She wore an elegant corselet that pushed up her modest breasts and bell-shaped skirts, which widened her hips, affecting the proportions of a fowl though he could see she was slimly built.

Their eyes met, and the girl’s expression was restrained, perhaps even sympathetic. Theseus had only hatred in his heart for any man or woman of Crete, but he felt himself veering toward her for a moment. She looked to be his contemporary. Minos’s daughter Ariadne, whose beauty was hailed around the world?

The king glanced at his priest, a silent exchange, and the horrible savage made an arcane gesture with his bony hands, grinned thirstily at Theseus, and bowed.

Minos declared, “If this is King Aegeus’s will, so shall it be done.” He gazed at Theseus like a lion with its prey beneath its paw. “But the terms of our agreement shall stand. You are but one son. Tomorrow, should you not emerge from the labyrinth with the beast’s collar by nightfall, it shall be sealed and your father shall owe me six sons and seven daughters of Attica to try the contest. I will not be denied what was promised to me. Or else I will turn my armada against Aegeus once again.”

In truth, the possibility of not surviving the contest had never lingered in Theseus’s head. His cause was just, and that was all. But now he pictured a black sailed ship wallowing through fog-banked waters toward harbor. Fathers huddled with their children on the pier, turning their heads away from the sight. His own father taking in the knowledge his son had failed and sentenced innocent children to certain deaths. His claim to save Athens no more than a foolish boast.

Theseus grasped for some counteroffer to the king. He could think of nothing.

The greedy king looked like he might break out in laughter. He knew Theseus had no leverage to negotiate further, and now that he had the king of Athens’ son in his clutch, he would likely devise more treachery to ensure the prince would not survive the contest.

~ ~ ~

Stop back on February 20th for Part Two of the story.