Most of us would agree that diversity and inclusion are good things. Perhaps especially in science fiction and fantasy (SFF), a white, cisgender, heterosexual male perspective has dominated the genre since the days of Jules Verne and H.G. Wells, and largely neglected fully-formed portrayals of women, people of color, and LGBTs, among other marginalized groups. Cultural marginalization creates political marginalization, and vice versa, so when all we see and read in SFF are worlds with white, male heroes, often populated solely by white people, it reinforces the belief that the dominant culture is superior, and the only norm; the rest of us are the “others.”

That tradition has changed somewhat through the success of celebrated female authors like Ursula LeGuin and Margaret Atwood and authors of color like Octavia Butler and Samuel Delany. Recently, N.K. Jemisin became the first black, female author to win the Hugo award for a novel, and three of the five titles that were shortlisted in 2016 were written by women. The annual output of SFF has become more diverse in terms of gender, ethnicity, sexuality and other characteristics, but surveys show we still have a long way to go to bring representations of people of color, women, and LGBTs out of the margins.

It’s hard to find data outside of the YA world, where, for good reason, a lot of the attention to diversity has been placed. The YA data I did find may or may not reflect the state of diversity in SFF as a whole.

For example, the Cooperative Children’s Book Center tracks a rising number of SFF books about people of color over the past few years, though in the last recorded year (2015), those books represented a little less than fifteen percent of all SFF releases. Regarding LGBT diversity, Malinda Lo’s most recent (2014) LGBT YA by the Numbers also showed a growing, yet still disappointing number of SFF releases about LGBTs: a total of seventeen in 2014.

CCBC also tracks how many SFF books are written by people of color, and that share is even smaller at ten percent. That gap in authorship is one of the reasons behind the #OwnVoices hashtag.

Started by YA author Corinne Duyvis in 2015, #OwnVoices was created to uplift books about marginalized groups that are written by authors who are members of that marginalized group. In addition to concerns about depth of characterization and accuracy, Duyvis says her interest in #OwnVoices grew out a collective concern that many minority authors who write about their own communities experience marginalization within the publishing industry, in the form of less recognition, lower advances, and less promotion than their privileged peers who garner kudos for writing diverse characters.

#Ownvoices supporter Ellen Oh tweeted home the point with the example: “Everyone knows Memoirs of a Geisha by Arthur Golden but not Geisha of Gion by Mineko Iwasaki.” In terms of queer SFF, you might say: everyone knows the gay wizard Dumbledore, created by J.K. Rowling, but not the gay wizard Jessex, created by Jim Grimsley (that observation is especially depressing since Rowling didn’t even write the character as gay, but she was lauded for promoting LGBT diversity just by saying she had envisioned him as gay).

Duyvis makes the important distinction that #Ownvoices refers to titles, not the authors themselves, since not all minority authors write about their own communities. It’s also not a campaign against authors outside of minority groups writing about minorities, who are often allies, but rather a campaign for uplifting #Ownvoices titles.

That point is important to me as I segueway into my analysis of #Ownvoices in queer SFF. A good number of authors writing about gay SFF characters, for example, are women, and as I’ve gotten involved in the queer SFF community, I have tremendous gratitude and respect for the many female authors who are my colleagues and my friends and my Twitter and Facebook “buddies.” They are a source of inspiration and have opened up opportunities for me as an author. Maybe it should go without saying, but repeating the point from the paragraph above, my interest in #Ownvoices in queer SFF is not to criticize female authors (or non-gay male authors) who write gay SFF or to suggest that they should not be doing it. I’ve read, and on occasion, participated in online discussions about appropriation and objectification, and I do think those are important conversations for authors and readers to have. The data I compiled, however, does not and is not meant to speak to those issues.

My purpose is to delve deeper into the state of queer diversity in SFF. Good and plentiful portrayals of queer characters are one dimension of progress, and one that many of us would argue could stand for some improvement. But authorship is important to consider as well. Queer authors have historically faced censorship and discrimination in the publishing industry (and beyond) when writing about queer experiences. Authorship is an aspect of diversifying literature that hasn’t been well-explored in a quantifiable way. If efforts to diversify literature seek to promote cultural fairness, I would argue, as #Ownvoices does, then they should acknowledge the differential experiences of privileged and disadvantaged authors who are writing diverse books, and seek to remedy the disparities that exist.

All segments of the queer spectrum need to be considered. I chose gay male SFF as an appropriate starting point because I know that genre most intimately as an author and as a reader, and I also have lived experience as gay man. By compiling some data on how gay SFF #Ownvoices titles fare in the publishing world, my hope is to begin to examine diversity from the perspective of authorship.

It would have been useful to count the number of gay SFF titles published each year by the big houses (Tor, Gollancz, Ace Books) and determine how many were authored by gay men, as a measure of disparity and “status.” Those big house titles have access to trade reviews, wide distribution, marketing, libraries, and awards programs to a far greater extent than small press and self-published titles. Unfortunately, I struggled to find data on the annual output of gay SFF books, and the prospect of researching the many hundreds of releases listed on the publishers’ websites was just too overwhelming; though I’m happy to cheer on anyone who endeavors to do that. 🙂

Malindo Lo’s meticulous investigation of big house titles, just in the YA world, those seventeen LGBT SFF books she found in 2014, are not identified by title or author or L or G or B or T. Lo also noted in her report she couldn’t estimate with accuracy proportionality with respect to the total number of published books due to the complexity of capturing that data.

A little easier to analyze are lists of books that are popular among readers, and recommended lists, and winners and finalists in awards programs. I decided those were decent places to gather data.

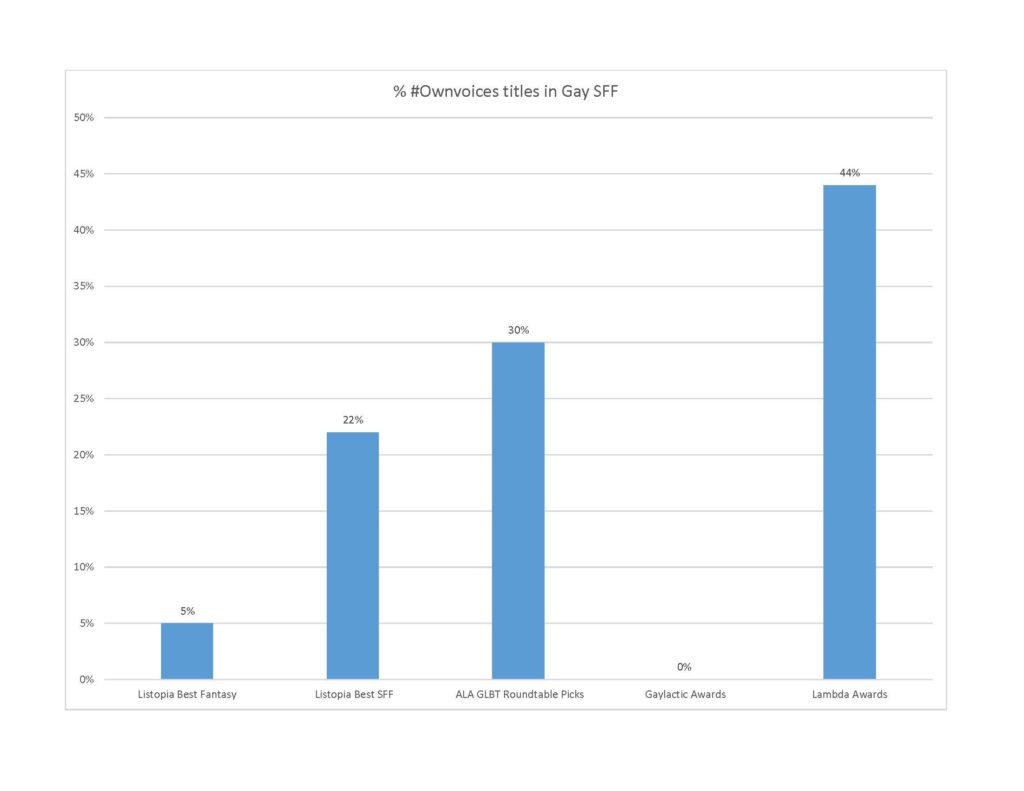

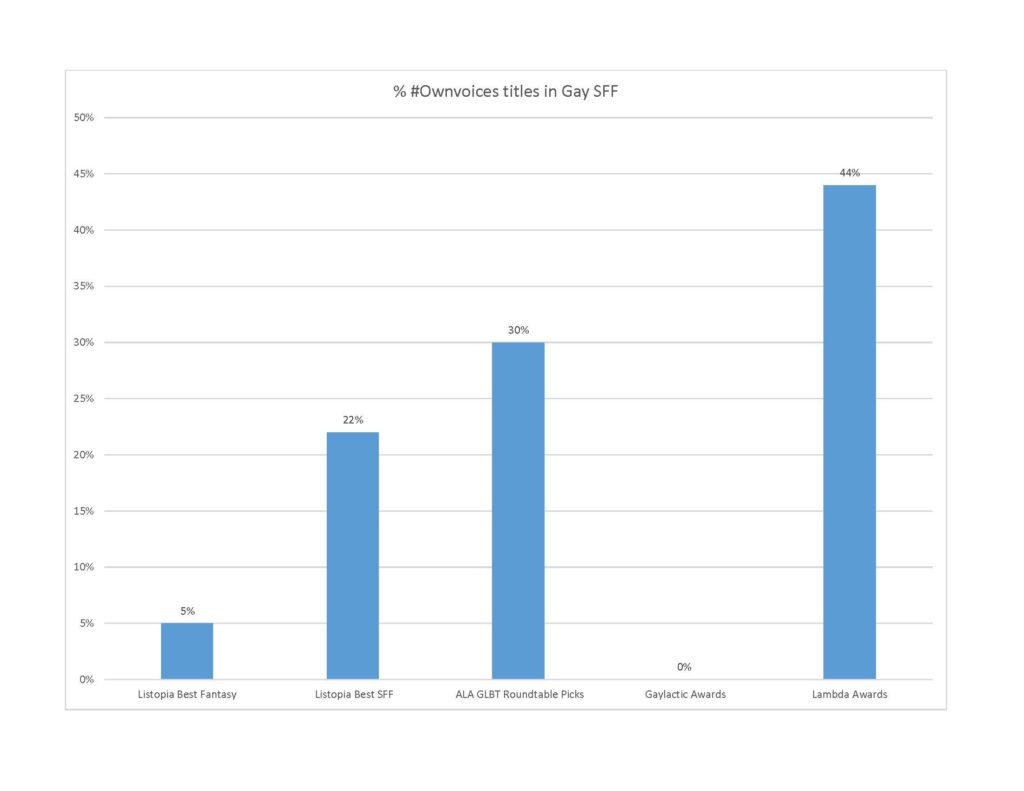

Looking at the top 100 books in Goodreads’ Listopia “Best Fantasy Books with Gay Characters,” 89 of the titles are authored by female authors, including the top ten. Of the eleven titles authored by male authors, five are authored by self-identified gay men, two are authored by a self-identified heterosexual man (Richard K. Morgan), and four are authored by men whose sexual identity I could not determine. That’s a rather paltry five, or at best nine percent share by #Ownvoices titles.

My method for determining an author’s gender and sexuality involved looking at biographies for pronouns and mentions of “husbands,” “wives,” or male “partners,” and in some cases delving into media interviews in which the author talked about his sexuality.

The fantasy Listopia leans toward “M/M” category romance titles like Lynn Flewelling’s Nightrunner series and Mercedes Lackey’s Last Herald Mage, so despite its title, the voters may not be so representative of the range of gay SFF readers and buyers.

So I also looked at the top 100 books in Goodreads’ Listopia “Best Science Fiction Books with Gay Characters,” where I found that 69 of the titles were authored by female authors. Twenty-two of the titles were authored by self-identified gay men, six are authored by heterosexual men, and three were authored by men whose sexuality I could not determine. That seems to indicate that sci fi #OwnVoices titles do a little better than their fantasy counterparts, though Goodreads members are still much more aware of, and/or enthusiastic about gay sci fi titles written by non-gay authors.

ALA’s GLBT Roundtable compiles recommended GLBT titles each year, based on “exceptional merit relating to the gay, lesbian, bisexual or transgender experience.” I analyzed their lists from the past five years (2012-2016). The Roundtable creates two annual “Over the Rainbow” lists: one for Young Readers and one for Adult Readers (18+). In the past three years, their Adult Readers list did not include any SFF titles. Their Young Readers list has more consistently included works of SFF.

In total, over the past five years, the Roundtable chose thirteen SFF titles featuring gay protagonists or secondary characters for its Young Adult list. Seven gay SFF titles figured into its Adult list for the years 2012 and 2013. Selections from both lists lean toward futuristic, dystopian and short story collections that are reflective of contemporary issues faced by LGBTs like religious and political persecution and coming out.

Out of those twenty selected titles, only six or 30 percent were authored by gay men. The Adult lists favored #Ownvoices titles a little more at 42 percent. The Young Adult lists included just three #Ownvoices titles out of thirteen books or 23 percent: Tim Floreen’s Willful Machines, Steven De Los Santos’ The Culling, and Alex London’s Proxy.

Another source I looked at was the Gaylactic Spectrum Awards. Their picks tend to be more “hard” and high concept SFF rather than M/M or books with educational themes. With its mission to: “honor outstanding works of science fiction, fantasy and horror which include significant positive explorations of gay, lesbian, bisexual or transgendered characters, themes, or issues,” you would expect to find lots of titles by gay authors on its shortlists, right?

Erm, not exactly. Spectrum nominees include a mix of lesbian, transgender, bisexual and gay male-themed titles, and of the twenty books with gay male protagonist or secondary characters that won awards or were shortlisted by Gaylactic over the past five years (2012-2016), exactly zero were written by gay men. Most were written by women, and two were written by heterosexual men.

Last, I looked at the winners and finalists at Lambda Literary Awards over the same five year period. The Lammys combine SFF and horror into one category, and, like Gaylactic, they don’t separate out the L, G, B or T. I did not consider horror titles in my analysis, and one challenge was that Lambda’s SFF picks lean toward literary speculative fiction, which in some cases defies conventional categorization, e.g. contemporary stories with some surrealistic elements (Robert Levy’s The Glittering World, Craig Laurance Gidney’s Skin Deep Magic) and stories that imagine gender and sexuality in fantastical ways (Mary Anne Mohanraj’s The Stars Change). I decided to include all of their SFF titles that contained some depiction of gay male sexuality, regardless of whether the SFF elements were “light” or “heavy.”

In total, I found eighteen titles that fit those criteria for the period of 2012-2016. Nine of the titles were written by female authors. Eight were written by gay male authors. One was written by a male author whose sexuality I could not determine. The upshot: 44 percent of Lambda’s picks were #Ownvoices titles.

Taken together, my analysis of five data sources seems to indicate that popular, recommended, and award-winning gay SFF titles are significantly more likely to be authored by non-gay authors, primarily women. The highest proportion of #OwnVoices titles I found was 44 percent within Lambda’s shortlist over the past five years. The lowest proportion was zero at Gaylactic.

And, wait for it…I made a chart!

More research is definitely needed. For example, I’ll be the first to indict my preliminary analysis as one dimensional. I have not as yet taken the time to cross-analyze the titles and authors I found by characteristics like race/ethnicity, which is immensely important to consider. I would hypothesize that #Ownvoices titles by gay men of color receive even less recognition than their white-authored counterparts.

My findings suggest there is indeed a gap between #Ownvoices titles and non-gay authored titles in gay SFF, and that gap appears to run across M/M romance titles (where one might expect to find the biggest disparity), but also, more surprisingly, titles with educational themes, “hard” and high concept SFF, and literary speculative fiction. The results also suggest that gay authors who are writing gay science fiction and literary speculative fiction may be having more success than those who are writing fantasy romance and high concept SFF. It raises a questions worthy of further exploration: why aren’t #Ownvoices gay SFF titles received by readers, librarians, and awards programs with at least the same amount of enthusiasm as gay SFF written by non-gay authors?