I’m often asked for fantasy recommendations, particularly on the gay fiction-side. That, combined with my love of the genre inspired me to tackle the project of putting together a list of titles as a departure point for readers looking for good quality portrayals of gay characters.

I could probably write an entire article on disclaimers about this list—the sea of titles to choose from, the subjective nature of singling out certain books, and the like. I actually kind of hate “best of” and “top ten” lists. They’re a bit disingenuous, so unnecessarily declarative, I think, and when I see them in magazines or blogs, I tend to be naturally cynical.

So, what should you take away from my little curated list? I guess just some ideas about what to check out if you’re new to gay fantasy, or even if you’re a huge fan and like comparing notes. I’m sure I missed some stellar books that aren’t on my radar. Feel free to let me know about those!

Disclaimer #2: These books are heavily skewed toward my reading (and writing) preferences, which are fantasy of the epic, historical, and/or magical sort, and more G than LBTQAI. I included one urban fantasy/superhero title and one magical realism. Those also happen to be the only young adult titles, and I only have one sci fi and one fairytale short story collection. Some of the titles have lesbian, bi, and trans characters. None represent Ace, Aro or Intersex. I called this “an intro to gay fantasy” because I don’t purport to have the literary cred to throw out recs across the queer spectrum, though I think there’s decent representation in terms of race/ethnicity.

Maybe I’ll work on updating the list for the future with more fantasy sub-genres. I really have to be in the right mood to read dystopian and futuristic sci fi. I make no promises.

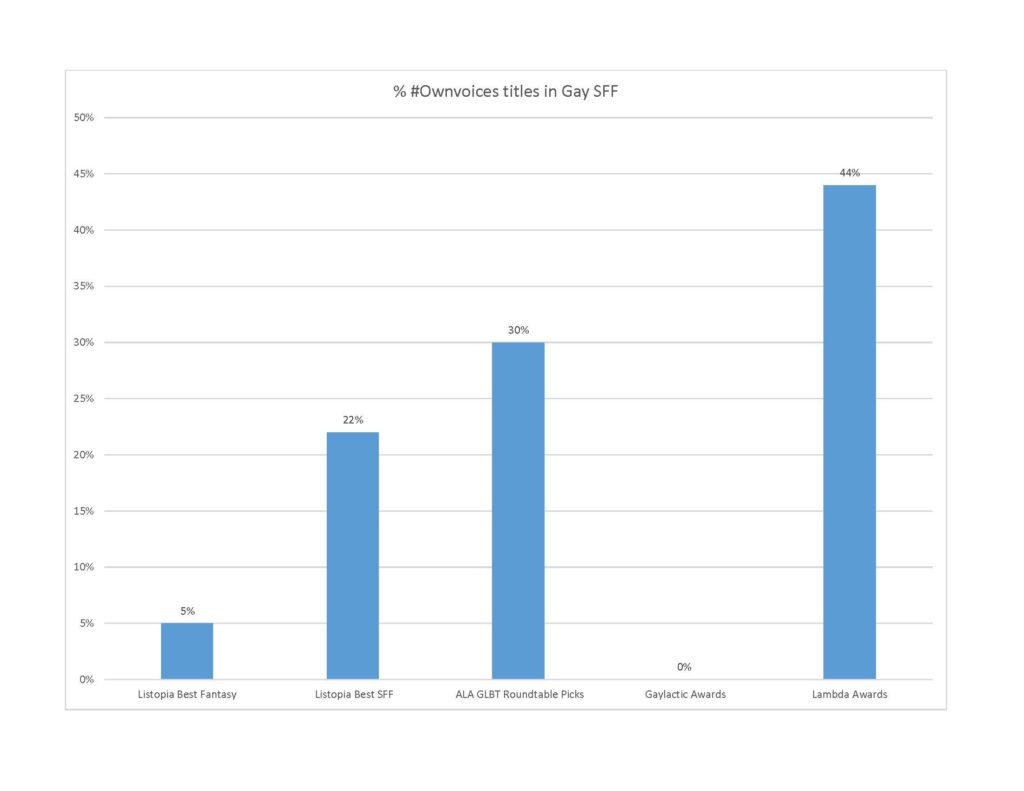

Last, I thought it was important to include why I thought each title was noteworthy, beyond my subjective appraisal since if I was in fact teaching a course on gay fantasy, that kind of thing would be important. You’ll see that down below. I also should mention I was intentional in choosing a diverse range of titles in terms of when they were written, the types of characters, themes, as well as #OwnVoices.

In a nutshell, #OwnVoices is a movement to uplift titles about marginalized groups, which are written by members of those marginalized groups, in order to combat historic and ongoing barriers for marginalized authors. I’ve written more about #OwnVoices previously if you care to learn more, and/or, check out this handy Q&A written by #OwnVoices creator Corinne Duyvis.

And away we go!

[12/9/2017 E.T.A. Chaz Brenchley’s Tower of the King’s Daughter. 2/10/2018 E.T.A. Lawrence Schimel’s The Drag Queen of Elfland. 3/20/2018 E.T.A. Philip Ridley’s In the Eyes of Mr. Fury. 4/19/2018 E.T.A. Ricardo Pinto’s The Chosen. 9/11/2019 E.T.A. Tom Cardamone’s Green Thumb]

The Left Hand of Darkness by Ursula Le Guin

Publisher: ACE

Year: 1969

Themes: Futuristic, science fiction, alien races, hermaphrodite/bisexuality, non-binary gender

Rationale for inclusion: Multi-awards: Hugo, Nebula; widely regarded as a groundbreaking and seminal work in SFF (see: reference); portrayal of bisexuality and reconstruction of gender

My quickie review: This won’t be the first or last rec list to begin with Ursula Le Guin. She was a prolific and critically-acclaimed author who brought feminist commentary on the construction of gender to the genre and opened doors for female authors. Of course, she’s also brilliant. The Left Hand of Darkness imagines an alien race that is neither male nor female, and undergoes a reproductive cycle (kemmer) during which they develop male/female genitalia temporarily and arbitrarily, resulting in many sexual combinations over the lifetime, including fairly universal pregnancy and ‘motherhood.’ That was a pretty wild and innovative concept for 1969, and though the story is seen through the eyes of a biologically male human Genly who is visiting this ‘ambisexual’ planet on a diplomatic mission (Genly also happens to be described as ‘dark-skinned’), the depth of development of the differently gendered world is extraordinary and engrossing. It is also a story that is interesting to look at in context. Le Guin has acknowledged that some of her own heterosexist bias crept in while imagining sexual preferences as well as ‘defaulting’ to an association between masculinity and authority/political power.

Tales of Neveryon by Samuel R. Delaney

Publisher: Bantam

Year: 1979

Themes: Ancient world, slavery/exploitation, gender roles, social justice, sexuality

Rationale for inclusion: Multi-award finalist: Locus, Prometheus, National Book Award; Groundbreaking for its time in terms of gay content; Critically acclaimed (see: Editorial reviews from Amazon page); #OwnVoices: Delaney is a black, gay man and the main characters of Neveryon are principally brown-skinned people, including a “gay” protagonist (see: reference)

My quickie review: Tales of Neveryon is a loosely-knit, rotating collection of narratives about people living in a pre-historic world that has hints of ancient Mesopotamia and Africa. My mind was blown when I discovered the book. It’s utterly immersive and brilliantly subversive. Hard to encapsulate the plot, but the principal character Gorgik is orphaned by war, fated to work in a mining settlement as a slave, and educated about the methods and immorality of the elite, ruling class when he is taken into an imperial court through chance circumstances. The scale of the world and its histories are epic, though it’s not precisely epic fantasy. Delaney plays the role of both philosopher and storyteller via parable-style vignettes that shed light on the human condition, from the inhumanity of slavery, patriarchy/gender roles, and even the origins of sexual kink (there’s a thread on sub/dom relations, which is more cerebral than erotic). Gorgik and his lover Small Sarg lead a revolution, earning the right to be called fiction’s first gay power couple.

Swordspoint by Ellen Kushner

Publisher: Arbor House Publishing (originally, later Tor and Spectra)

Year: 1987

Themes: Regency era inspiration, swordfights/dueling, gay and bisexual relationships

Rationale for inclusion: Critically acclaimed (see: Editorial Reviews from Amazon page); Groundbreaking for its time in terms of gay content; Fan favorite (see: Listopia)

My quickie review: One of the most highly praised examples of “MM fantasy romance.” Though I would not lump Swordspoint in with modern “MM.” The story has dark romantic elements, but there’s much more going on beyond the sexual and romantic lives of the characters. The setting itself is strange and subtly textured. It has an “almost” quality – familiar in its portrayal of greedy ‘haves’ and squalid ‘have-nots,’ a mannerly Regency Era world where grievances are settled by duels and people dress for tea. Yet there’s just enough queerness, and unique geography, to make you realize this isn’t Oxfordshire in the 18th century. The story centers on St. Vier, an expert swordsman with a host of wealthy patrons vying for his services, or to destroy him, in order to settle their petty feuds. Just about everyone is morally suspect, which makes for great drama and characters you love to hate. Kushner accomplishes quite a lot in this story of excess, greed, vanity and exploitation, including an unexpectedly compelling gay love story.

In the Eyes of Mr. Fury by Philip Ridley

Publisher: Penguin (originally), re-released by Valancourt

Year: 1989 and 2016 respectively

Themes: 1980s, coming of age, magical realism, young adult, urban and historical legend

Rationale for inclusion: Award-winning author (most notably for screenplays The Krays and stage plays); groundbreaking in its young adult-style portrayal of gay adolescence; #OwnVoices: Ridley is a gay man and his story is a semi-autobiographical gay coming of age tale (see: reference).

My quickie review: Before he was one of Britain’s preeminent playwrights, Ridley penned what I consider an astoundingly, ahead-of-its-time, unabashed story of gay adolescence, incorporating magical elements that I’d also say are prescient of the wondrous imagination of J.K. Rowling. He expanded the story in 2016 to create “the world’s first LGBT magical realism epic,” which is the version more widely available. Eighteen-year-old Concord is a gay kid in the working-class East End of London in the 1980s, and the mysterious death of a notorious curmudgeon up the street leads him into a magical journey, chaperoned by the eccentric Mama Zepp, through which he discovers neighborhood secrets, including the gay men and women who came before him. Mama Zepp’s collection of antique eyeglasses turn out to be something like Viewmaster devices for beholding scenes from the past, and her tea biscuits can summon the departed to tell their stories. It’s not all pretty for Concord looking back on how gay people lived, nor confronting how he himself can live, but when an unusual young man, accompanied by a protective crow, enters the neighborhood, first love may help Concord transcend the horrors of the past and present. An immensely charming story for readers of all ages.

The Drag Queen of Elfland by Lawrence Schimel

Publisher: Circlet

Year: 1997

Themes: Retold fairytales, short stories, AIDS, vampires, werewolves

Rationale for inclusion: IPPY Finalist (1998); award-winning author and editor; portrayal of HIV+ characters; #OwnVoices: Schimel is a gay man and his collection is primarily stories about gay men (see: reference).

My quickie review: Schimel’s short story collection is a wonderful illustration of how fantasy can be used as an atmosphere for exploring gay and lesbian situations. The fairytale setting is an appealing context for stories of young love, whether against-the-odds triumphant (“Fag Hag”) or earnest and painfully unrequited (“Heart of Stone”). The gothic or paranormal theme lends itself quite nicely to tales of loneliness as with “Take Back the Night,” in which an older lesbian who owns an all-night feminist bookstore is visited by a werewolf and tempted to literally become a woman who runs with the wolves. I loved Schimel’s choice of featuring gay men living with AIDS (“Hemo Homo”) and “femme” gay characters (“The Drag Queen of Elfland,” “Coming Out of the Broom Closet”). While those stories are rooted in an historical context, they bring attention to issues of positionality re. serostatus and gender expression that remain highly relevant in the gay male community.

Tower of the King’s Daughter by Chaz Brenchley

Publisher: Ace

Year: 1998

Themes: Knights/Crusaders, Arabic folklore, religious persecution, magic, gay relationships

Rationale for inclusion: British Fantasy Award; Critically acclaimed (Starburst, Locus Magazine)

My quickie review: I only read this second book in Brenchley’s Outremer series as sadly, the series is out of print, and some confusion between the British and American editions led me to the Tower first. But I highly recommend it if you can get your hands on a copy from the library. The story takes inspiration from the Crusades, set in a desert kingdom where righteous ‘Ransomers’ clash with the native Sharai who have the gift of an arcane magic. A central POV character is the young, gay squire Marron, who is finding his place in the world amid his religiously fanatical countrymen, a band of insurgents with fantastical powers, and his master Sieur Anton D’Escrivey, who shares his persecuted gay identity. Brenchley’s writing is an engaging blend of quiet, introspective characterization and vivid action scenes.

The Chosen by Ricardo Pinto

The Chosen by Ricardo Pinto

Publisher: Tor

Year: 1999

Themes: Ancient world, royalty, slavery, fantasy creatures, young gay relationships

Rationale for inclusion: Gaylactic Spectrum Award finalist; Critically acclaimed (Strange Horizons, SF Site Reviews); #OwnVoices: the main character’s storyline involves a gay male relationship and the author is a gay man, vis-à-vis the book dedication to his husband.

My quickie review: Described as “low fantasy,” meaning no swords or sorcery, Pinto’s début novel and first book in the Stone Dance of the Chameleon attains its magic via a brilliantly imagined fantasy world that reads at times like it’s spun out of terrifying, fever dream. Pinto touches on ancient world sensibilities, but really the setting is one-of-a-kind. An aristocratic class (the titular ‘Chosen’) live lavishly, grotesquely, supported by a slave economy and caste system codified by gods-given edicts. That may not sound so new and innovative, but to see is to believe as Pinto draws the reader into a world of bizarre rituals, impossibly extravagant costumes, and strange beings who serve the royal court such as conjoined ‘syblings’ and the blinded undead who live in symbiosis with homunculus creatures. Carnelian, the fifteen-year-old heir to a royal house, is coming of age while a new god-emperor must be chosen through a complex and treacherous political process, which Carnelian’s father must oversee. In spite of his privileged status, he makes for a compelling lead—sensitive yet unafraid to stand up for himself, and an attempted assassination of his father propels him on a journey of increasing danger and isolation. Along the way, an encounter with a mysterious boy in a pitch dark, forbidden library leads to a tender, triumphant, and high stakes love story. This one hits all the marks for me.

Kirith Kirin by Jim Grimsley

Publisher: Meisha Merlin

Year: 2000

Themes: Elemental magic, coming of age, gay relationships

Rationale for inclusion: Multi-awards: Lambda Literary Foundation (winner), Gaylactic Spectrum (finalist); #OwnVoices: author is an openly gay man and the main characters are gay (see: reference).

My quickie review: Grimsley’s approach to fantasy is earthy, atmospheric and mystical, and reminded me a bit of Ursula Le Guin’s Wizard of Earthsea. He is also extremely meticulous. The story is a nearly day-to-day account of the magician Jessex’s apprenticeship and the eventual mastery of his powers. There’s not a lot of sword and sorcery as that’s not the story’s style. Jessex is kind and gentle and fights the battles that he must through a complex command of magic involving sacred songs and the manipulation of time and space. The book is at least equally a love story (Jessex and the titular Kirith Kirin) and a coming-of-age adventure. I thought the romantic storyline was sweet, surprising and accessible.

Mordred, Bastard Son by Douglas Clegg

Publisher: Alyson Books

Year: 2006

Themes: Arthurian legend, magic, coming of age, gay relationships

Rationale for inclusion: Critically acclaimed (see: Editorial reviews on Amazon page); Somewhat of a ‘cult favorite’ from a popular horror author; #OwnVoices: author is an openly gay man and the main character is a young gay man (see: reference).

My quickie review: Where Samuel Delaney blew me away with how provocative gay fantasy can be, Douglas Clegg’s retelling of the King Arthur legend blew me away with how fabulously subversive gay fantasy can be. Here, Clegg takes a despised character from a beloved canon, and tells his story in an inexorably sympathetic way. I think of it as a particularly noteworthy achievement in that traditional Arthurian legend is so stridently heterocentric. Evil, fey Mordred has been the inspiration for countless tales of queer villains, the archetypical foil to the righteous, sword-wielding, damsel-in-distress loving hero, repeated ad finitum in SFF. Clegg’s story is more than just a skewering of that narrative. It is a poignant story of a boy alienated from the human world because of his strange magical abilities and alienated from his own magical kin because of his queerness. And he has an affair with Lancelot. Read this book now!

Wicked Gentlemen by Ginn Hale

Publisher: Blind Eye Books

Year: 2007

Themes: Demons, persecution, mystery/crime, steampunk, gay romance

Rationale for inclusion: Gaylactic Spectrum award; Fan favorite (see: Listopia).

My quickie review: An immensely dark tale premised on the existence of an ancient demon race whose descendants are persecuted and exploited by an authoritarian, religious fanatic regime. That may sound rather “on the nose” for gay fantasy allegory, but this is quite a sophisticated novel that doesn’t veer into sentimentality or preachiness. Bellamai, who has demon blood, must team up with Captain William Harper who is tracking down a serial murderer and needs an expert who can help him navigate the seedy underground, aptly called Hell’s Below. There’s a complicated romance between the two men and lots of action, suspense and creepy atmosphere along the way.

Hero by Perry Moore

Publisher: Disney-Hyperion

Year: 2007

Themes: Superheroes, coming of age, coming out

Rationale for inclusion: Multi-awards: Lambda Literary Foundation Award winner, Gaylactic Spectrum finalist, Inky Awards finalist; Groundbreaking portrayal of gay superhero in teen literature; #Ownvoices: author (deceased) was a gay man and the main character is a gay youth (see: reference)

My quickie review: I’m coming out as a fantasy reader who is not a comic geek, which explains the paltry number of superhero titles on my list. What drew me to read Hero was the story behind the story. Perry Moore was a crusader for fair treatment of LGBTs in comics and SFF, and beyond the book he wrote, his outspoken, tenacious advocacy opened doors for LGBT superhero creators in the industry. The book is lovely. Closeted teen Thom Creed is trying to stay below the radar in a homophobic, working class town, and living with a gruff, single dad who was disabled by an accident. When Thom discovers he has magical abilities, he reluctantly and secretly joins ‘the League.’ There’s a boy he’s crushing on, but their encounters are always bittersweet near misses, along with lots of comic in-jokes and a simmering battle with the bad guys in the background.

The Steel Remains by Richard K. Morgan

Publisher: Gollancz (originally, later Del Rey)

Year: 2008

Themes: Sword and sorcery, slavery, persecution (including persecution of gays), gay relationships

Rationale for inclusion: Gaylactic Spectrum award; Commercially successful ‘crossover’ to mainstream SFF

My quickie review: Fantasy does not get much darker than The Steel Remains, so if you’re looking for an uplifting, gay-themed story and/or are squeamish about graphic violence including rape and sexualized torture, this is not the book for you. In fact, I vacillated about including The Steel Remains on my list because the two principal gay characters’ queerness is largely a source of hardship, persecution, and tragedy, a problematic treatment you can find far and wide in SFF. Still, two of the three rotating protagonists are unabashedly gay: Ringil, an emotionally and physically hardened male warrior, and Archeth, a tightly-wrapped, female dignitary of a mystical race, and the fact that their stories are front-and-center in a ‘popular’ market epic fantasy is something of an achievement for sure. The two must navigate a corrupt, war-torn world, which may be further unraveling by the return of an ancient race of magical demons. The writing is terrific, and the constant sense of danger makes the book a page-turner.

Ash by Malinda Lo

Publisher: Little Brown

Year: 2009

Themes: Retold fairytale; Medieval setting; fairies; lesbian relationships

Rationale for inclusion: Multi-award nominee: Lambda Literary Awards, Gaylactic Spectrum, William C. Morris for Début Young Adult fiction; Critically acclaimed (see: Editorial reviews on Amazon page); Commercially successful; #OwnVoices: author is an Asian, lesbian woman and the main character is a young lesbian (see: reference).

My quickie review: The tagline is: “Cinderella retold,” but this is quite a freshly imagined tale that charms the reader with its subtlety and eloquence. Lo pays tribute to the original source in clever ways: her use of language (the titular heroine Ash) and gender-swapped characters (a fairy godfather; a female “woodsman”), and the world and characters are much more complex than the good vs. evil conventions of classic fairytales. A convincing portrayal of an orphaned girl’s very high stakes struggle to live in an unsparing, feudal country with dangers arising from tradition as well as an intriguing, hidden magical world.

The Way of Thorn and Thunder by Daniel Heath Justice

Publisher: University of New Mexico Press

Year: 2011

Themes: Indigenous folklore/mythology, elemental magic, fantasy creatures and fantasy ‘races,’ war, persecution, two-spirit, gay relationships

Rationale for inclusion: Portrayal of people of color in fantasy; #OwnVoices: author is a Native, gay man and many of the characters are Native and non-heteronormative (see: reference).

My quickie review: This full-on Indigenous fantasy epic spans years and many miles in an engrossing story of a pre-historic America filled with magic and fantasy races and more political themes of cultural exploitation and extermination. Told through the rotating and intersecting journeys of ‘Kyn-folk’ characters, it is the story of the struggle to protect the ‘Everland’ from Men who would exploit and enslave its people and its sacred lands. Same-sex relationships and non-traditional gender roles among the ‘Kyn’ are portrayed matter-of-fact, and there’s a two-spirit character, a tribal healer, who is partnered with a male chief. As an allegory for the real, current and historical atrocities against Amerindian peoples, it is one of the most compelling heroic fantasies I’ve read.

Green Thumb by Tom Cardamone

Green Thumb by Tom Cardamone

Publisher: Lethe Press

Year: 2012

Themes: Post-apocalypse, dystopia, futuristic, “new weird fantasy,” mutation, gay relationships

Rationale for inclusion: Lambda award for SFF; Critically acclaimed (see Editorial reviews on Amazon); #OwnVoices: author is a gay man and the principal characters are gay men (see: reference)

My quickie review: I mentioned in my lead-in I’m not a huge fan of post-apocalypic, dystopian stories, but Green Thumb is such a brilliant testament to the power of the queer imagination, it surely belongs on a list of stand-out fantasy reads. The subject is near future biological catastrophe, and the lead character Leaf is described as a boy who eats the sun. Anthropomorphic and polymorphic characters abound. Leaf’s friends are a scaly skinned boy called Scallop and a manta ray-human hybrid called Skate. Leaf himself is more plant than human in constitution, but much more human than plant in emotion. Cardamone pushes boundaries in eroticizing the grotesque, yet the story is grounded in a sense of humanity for all things freakish, even achieving a sense of poignancy in its portrayal of young love. The writing style is lyrical and psychedelic, reminiscent of William S. Burroughs to me, thus it’s one wild, weird, wondrous and at times disturbing romp.

The Sorcerer of Wildeeps by Kai Ashante Wilson

The Sorcerer of Wildeeps by Kai Ashante Wilson

Publisher: Tor

Year: 2015

Themes: Demigods, sorcerers, African-inspired setting, gay relationships, fantasy creatures

Rationale for inclusion: Crawford award; Portrayal of people of color in fantasy; #OwnVoices: author is a black, gay man and the principal characters are black, gay men (see: reference)

My quickie review: A fantasy adventure strong on style and literary “voice.” The main character Demane and his love interest the Captain are demigods. Demane is also a sorcerer with a magical ability to heal. Different from traditional fantasy, we don’t see much of what that means on the page, and the spare storyline is an expedition into the wild to kill a lion-like beast called the junkiere. What you do get is lyrical passages and effective dialogue that grounds the reader in a wondrous world of Wilson’s imagination.

The Chosen by Ricardo Pinto

The Chosen by Ricardo Pinto

Green Thumb by Tom Cardamone

Green Thumb by Tom Cardamone The Sorcerer of Wildeeps by Kai Ashante Wilson

The Sorcerer of Wildeeps by Kai Ashante Wilson