I recently received a comment on my 2016 report on the State of #OwnVoices in Gay Fantasy. Then, I saw a lot of Twitter chatter about #OwnVoices in response to Helene Dunbar’s upcoming YA title about a gay boy coming of age in the early years of the AIDS epidemic, of which she made the unfortunate claim that no such stories have ever been written before.

I HAVE NEWS!!!

So thrilled to be working on this book with @EditorALB & @SourcebooksFire! More about this 1983 NYC story about love & fear in the very early days of the AIDS crisis, here:https://t.co/FyK0NiNLPk

— Helene Dunbar (@Helene_Dunbar) May 8, 2018

Then, I saw an author sharing a list of #OwnVoices titles in adult fantasy to make the excellent point that the YA community has organized well to bring attention to diverse authors, but the adult fantasy world, not so much. (And sadly, to that point, I promptly lost the reference on my Twitter feed. Maybe the thread disappeared.)

All of that was enough to push me to revisit the topic and share some of my latest thoughts.

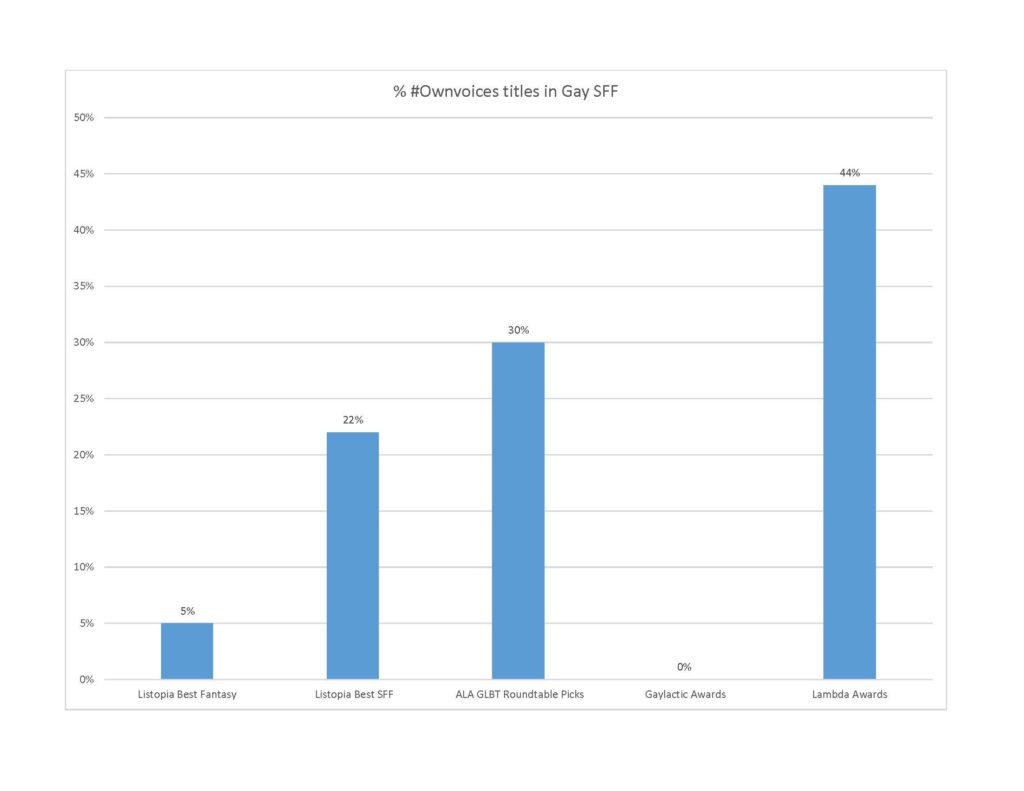

I won’t rehash all the data from my first look at #OwnVoices since you can read the (fairly) short article here. In brief, I looked at authorship of gay fantasy titles across three dimensions: popular books, recommended books, and award-nominated books. For popular books, I took data from two Listopia lists: Best Fantasy Books with Gay Main Characters, and Best Sci Fi Books with Gay Main Characters. For recommended books, I took data from the ALA’s Over the Rainbow Lists for Young Adults and for Adults. For award nominated books, I took data from the Gaylactic Spectrum Awards and the Lambda Literary awards (the Lammys) for Best SFF/Horror.

#OwnVoices titles ranged from zero to forty-four percent, and were more likely to be found in award-nominated and recommended lists. My analysis included data from the period of 2012 through 2016. I didn’t drill down on intersectionality, i.e. titles written by gay authors of color, though my guess would surely be the tiny slice of titles by those authors is quite troubling. I’m just a little wary about trying to quantify that with accuracy, and I don’t have the resources to survey authors. It’s become somewhat of a norm for gay authors to say they’re gay (or have a husband) in their bios, but not so much that they’re black or white or Asian, etc.

So now it’s a little over one year later. Has anything changed? Can we glean anything more by looking at other sources? These were my curiosities, so I took another look.

Goodreads’ Listopia lists are established by reader votes as well as the number of ratings and the average rating for each title. From my periodic perusal, they don’t change so dramatically from year-to-year. But to the extent new titles come out all the time and can shuffle things around a bit, I thought it was worthwhile to look at the same lists I analyzed back in 2016.

In 2016, the top 100 titles in Best Fantasy Books with Gay Main Characters included five #OwnVoices titles and four titles by authors whose sexual identity I could not determine. So, somewhere between five to nine percent were #OwnVoices.

My snapshot of the same list from a couple of days ago included eight #OwnVoices titles and one title by an author whose sexual identity I could not determine. As in 2016, none of those titles were in the top 10. Only one was in the top 40 actually (Jesse Hajicek’s The God Eaters). This shows a slight improvement, I guess. #OwnVoices are up to eight to nine percent of popular gay fantasy titles on Goodreads versus five to nine percent in 2016.

In 2016, the top 100 titles in Best Sci Fi Books with Gay Main Characters included twenty-two #OwnVoices titles and three undetermined titles. My more recent look: twelve #OwnVoices titles and seven I could not determine. That’s a drop from 22-25% to 12-19%. The results from that list are even more dismal when you consider some of the highest-ranked titles are popular sci fi books that don’t even have gay or bi lead characters, e.g. Frank Herbert’s Dune?

But, onward we go.

To expand my survey of popular titles, I bit the bullet and looked at an Amazon Best Seller list. I’d been skeptical about using that data source since gay fiction bestsellers on Amazon are notoriously strange, overrepresenting titles from their self-publishing platform, and heavily skewed toward erotica, regardless of the purported categorization.

Another problem is the ranking algorithm favors recent releases as it relies on predictive data. Many of us authors have experienced a new release popping up at the top of the charts because books get the most sales around release time. But Amazon treats that as a predictor of how many sales the title will get on an hourly basis, and typically over weeks, months, or years certainly, that once best-selling title takes a dramatic plunge in the charts based on actual buying behavior over time.

I’m still a bit skeptical about what the data tells us, but I thought it would be interesting to take a look at the titles and authors. So I pulled up one list, which is of course just a snapshot in time: Top 100 Best Sellers in LGBT Fantasy.

While there are a few L and T titles included, it definitely leans heavily toward stories with gay or bisexual male leads. I only considered those books when parsing out #OwnVoices titles.

I found eight #OwnVoices titles in the top 100. Twelve others appeared to be written by men, but I couldn’t determine if they were gay or bisexual.

A brief aside: This time around, I was slightly less assiduous in researching author sexual identity while also more conservative about counting an author as gay or bisexual. For one thing, when an author’s bio doesn’t say he’s “openly gay/bi,” it’s tedious work, combing through the media surrounding each author, looking for mentions of a husband or a coming out story. For another, the use of author pen names and fictional identities makes the research even tougher, and sometimes unreliable, with the stark possibility there are even fewer titles written by gay/bisexual male authors. (FYI, I had counted Santino Hassell’s books as #OwnVoices in my last report).

My conclusion, however questionably supported, is that Amazon best seller titles trend similarly to popular gay SFF on Goodreads: between 5-20% are #OwnVoices.

Next, taking a look at recommended lists.

ALA’s GLBT Roundtable had thirteen gay/bi male SFF titles on its Over the Rainbow List for Young Adults during the period of 2012-2016. Three of those were #OwnVoices. Their Over the Rainbow List for Adults had only seven gay/bi male SFF titles in the same time period and three were #OwnVoices. Overall, #Ownvoices made up a 30 percent share.

For 2017, the list for Young Adults included four gay/bi SFF titles. Two were by Rick Riordan. The other two were #Ownvoices. The Roundtable chose zero gay/bi SFF titles to include on its 2017 recommended list for adults. That list favors contemporary coming out stories, especially in underrepresented communities.

I tried to find another decent source to analyze recommended gay SFF titles, but it’s really the wild west out there on the interwebs. I mean, there are a lot of click-bait articles like “Seven must-read fantasy books with kick-ass queer heros/heroines,” but they’re so idiosyncratic and in some cases self-promoting, they don’t seem worth analyzing. If you’ve got an idea about where I should be looking, let me know.

Now for the major awards programs in queer SFF. Shockingly and disappointingly, Gaylactic continues to not be able to find a single #OwnVoices gay/bi male SFF title worthy of their consideration. I mean zero. They had zero from 2012-2015, and they had zero in their most recent (2016) awards program.

Lambda Literary Foundation does better. They had 44 percent #OwnVoices titles in their short lists for Best SFF/Horror 2012-2016. 2017 is a different story.

Now I should say, the number of Lammy SFF/Horror finalists for 2017 is small: eight titles; and it’s a mix of lesbian-themed, bisexual-themed, transgender-themed, non-binary themed, and gay-themed titles that all sound fascinating, worthy of recognition, and nicely representative of authors of color. Also, they favor titles with overlapping themes that explore gender in really interesting ways and in many cases include all kinds of variations of same-sex and poly and “queer” relationships (human/android for instance in Annalee Newitz’ Autonomous). They lean, of course, toward literary fiction versus genre fiction, and I’d say style/high concept versus action-adventure/plot-driven works.

So, my analysis was a little knottier, but based on four of the titles that feature a leading gay male oriented character (often along with other non-traditional gender constructions and lesbian characters) and based on only one of those titles being authored by a self-identified gay man, I’m saying 25% of their finalists are #OwnVoices.

This may be a good time to step back from the data and reconsider the question: why is #OwnVoices in gay SFF important? I mean, on one hand, you could say that queer representation in the genre has increased, such that readers can more easily find books by popular authors about queer people, some by household names. Rick Riordan is one example.

Furthermore, you could say SFF by definition is experimental and exploratory (speculative). SFF stories have stepped outside of gender/sexuality norms for decades, led by big name authors like Robert Heinlein, Ursula Le Guin and Samuel Delaney. Then, you could also say we’re happily beginning to see greater representation of non-binary, trans, poly, lesbian, queer people of color—all of which have been overlooked in SFF to a far greater extent than gay or bi male portrayals. Lambda’s choices of finalists may reflect an effort to elevate those stories and those voices, and I’d say it’s appropriate for white, gay, cis gender male authors, and our titles to step aside for the sake of cultural fairness. #OwnVoices is, after all, a movement to redress historical barriers to publication.

Related to that point, you could say, if you look at gay/bi male authorship more broadly in the fiction world, and specifically at white, cis gender, gay male authors, there’s evidence that we face less barriers to publication, recognition, and awards than other writers beneath the QuILTBAG umbrella. Take for instance this year’s Pulitzer Prize winner for fiction: Andrew Sean Green. Many of the most successful authors writing LGBT YA are white, gay, cis gender men as well: David Levithan and Bill Konigsberg, for example. Historically, white men have been privileged in the publishing industry and continue to be. White, gay, cis gender male authors benefit from that privilege, so redistributing power to female, lesbian, trans, and non-binary authors, especially those of color, is important from a social justice perspective.

For all those reasons, you could argue the #OwnVoices cause lacks relevance for gay, cis gender male titles, just as few would argue we need more hetero, cis gender male titles written by hetero, cis gender men in order to even the scales. And I do think that point-of-view is important to the discussion.

Though I also think something different has happened in queer SFF, and it’s unrelated to the publishing industry’s intentional elevation of underrepresented queer voices, which is slowly occurring in contemporary adult fiction and YA. If that were the case, we’d see a queer SFF landscape that includes a diverse range of queer authors: gay, transgender, lesbian, bi, black, Latinx, Asian, Native, etc., and while there’s some evidence of that via awards programs (and to a limited extent in ALA’s curated titles), the authorship of popular queer SFF titles, which are naturally in the broadest distribution, is not so inclusive, and has never favored gay/bi male authors, even as gay/bi characters are much more common than other queer portrayals.

Pre-1990s I’d say, with wonderful, notable exceptions like Samuel Delaney, gay/bi portayals predominantly came from best-selling, heterosexual male and female authors (Richard Heinlein, Ursula Le Guin, Marion Zimmer Bradley, among others), and that tradition is still a factor in whose gay/bi stories get published (Ian McDonald, C.S. Pascat, Cassandra Clare, as some more recent examples). In the late 90s and early 2000s, female-authored “M/M” romance/erotica emerged as an important market, with popular subgenres in romantic sci fi and fantasy, and nowadays M/M fantasy is the most prolific, sought-after category of queer SFF, which has implications for what kinds of titles get published, what kinds of authors get published, and even how we talk about queer literature.

It’s not just an issue for SFF. One recent example is LGBTQ advocates’ reaction to Helene Dunbar’s upcoming title.

Saw the great conversations earlier regarding own voices m/m YA and while there are certainly things I could say about that, right now I want to highlight some of the #ownvoices m/m YA that I’ve have edited (a non-exhaustive list!):

— Andy (aka Michael) (@cupcakeandy) May 9, 2018

Um, #OwnVoices M/M YA? I realize M/M has become shorthand for stories with gay male characters, but using that terminology in the #OwnVoices context is kind of absurdly problematic. M/M was created as homoeroticism “by and for women.” I’ll link in some references here:

What I fear many younger authors don’t understand is M/M was never intended to be a space for gay male authors to write about their own communities. And that before and after M/M existed, gay authors have been writing gay stories that some of us still call gay fiction, or gay romance, or gay fantasy, etc., because, well, they’re stories about gay people. The idea that gay authors need to be uplifted in the M/M fiction market, or need help ‘breaking into’ it, is a rather frightening statement on our positionality in the gay publishing industry.

All right. I’m going to very consciously set aside my personal feelings about M/M and focus instead on the story told by the data. Instead of looking at titles that are popular, win awards, and are otherwise recognized as merit-worthy, what about looking directly at the lists of titles coming out from publishers?

The biggest publishers of SFF, Tor and Gollanz for example, are unfortunately difficult to analyze because their output is so large, and at least as far as I’ve been able to determine, no one is quantifying the number of queer titles that get released on an annual basis. I spent some time on publisher websites, trying to use their search fields to call up titles with keywords like “gay” and “queer.” They’re not set up to generate the kind of information I’m looking for. For example, a search of “gay” at Tor’s webstore inexplicably brings up blog entries about “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow.” So, not so useful.

The main small presses that publish queer SFF have websites that are much more conducive to my purposes. You can browse titles by genre or ‘pairing,’ and see every title in their recent releases and backlist. So I looked at two of the biggest publishers of queer SFF in the small press world: Dreamspinner and Pride Publishing. There are others for sure, like Blind Eye Press, Bold Strokes Books, Less Than Three, and NineStar Press, but their collective output is dwarfed by those two big publishers with regard to SFF.

Dreamspinner published 100 gay SFF titles from October 5, 2016 – May 15, 2018, which is a pretty impressive output for a little over a year and a half period. Of those titles, I found fourteen which could be confirmed as authored by gay/bisexual male authors, and half of those were by two authors: Eric Arvin and T.J. Klune. I found four titles by authors who identified as male but whose sexuality I could not confirm. The upshot: 14-18 percent of Dreamspinner’s gay SFF titles were #OwnVoices.

Pride Publishing has a smaller output and tags their titles a little differently. I pulled up their last 100 gay fantasy/fairytales or gay sci fi titles, which covered the period of 2013-2018.

Just one author in that list appears to be male, and I could not determine that author’s sexuality. Thus, between zero and 1 percent of Pride Publishing’s gay SFF titles are #OwnVoices.

I think that data is a pretty good indicator that very few small press gay SFF titles are #OwnVoices. I didn’t take the time to analyze the content of the titles, but I’ll just say, unscientifically, based on the cover art, there is a preponderance of titles that are marketed as romance/erotica (M/M). But that would make for a good follow-up question to explore: how many gay SFF titles are first and foremost M/M romance versus SFF? Additionally: how many gay SFF titles feature characters of color and how many are written by gay/bi authors of color?

I’d love to come up with a way to analyze gay SFF in mainstream publishing, quantifying how many titles Tor and Gallanz and Penguin are putting out each year and take a look at authorship. Those publishers represent the harder, more epic, more adventure-driven edge of SFF, and it would great to say with some authority if #OwnVoices titles fare better or worse there. If anyone has any ideas that might be less tedious than analyzing their entire list of SFF titles, toss them my way!

I also think good information could be collected by doing a survey of gay/bisexual male authors as well as publishers of gay SFF. That would provide some data on racial diversity, who’s represented in publishing houses, and what concerns authors and publishers themselves have about #OwnVoices.

As a starting point, if you’re a gay/bisexual male author or a publisher of gay SFF, feel free to drop me a comment or an e-mail if you prefer.