It’s that great time of the year when the American Library Association (ALA) celebrates the right to read without censorship. As an author and a reader of gay literature, I have a big stake in that. Books about LGBTs are particularly vulnerable to challenges by misguided factions of the public, particularly books for children and young adults.

I’ve never had any of my books challenged to my knowledge, though maybe that’s because my books could use a boost of discoverability (which is why you should ask your library to purchase eight or fifty of my titles for their collection). But if The Seventh Pleiade or Banished Sons of Poseidon was challenged because of homosexual content, they would be in prestigious company. Some of the most frequently challenged books for “homosexuality” include Stephen Chbosky’s Perks of Being a Wallflower and Alice Walker’s The Color Purple.

ALA’s list of the most frequently challenged books includes a lot of impressive titles, many of which have been staples in english literature classes from grade school to college. To join with public libraries in raising awareness, I thought I’d share some of my favorite “banned books.”

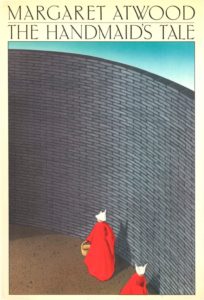

Banned for: sexual content and being offensive to Christians

I read Atwood’s feminist, dystopian sci fi novel during my cynical, anti-establishment college years, which, come to think of it, has stretched into my 40s. I loved that the story is in the high concept, dystopian vein of some of my other favorite futuristic books (Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World and George Orwell’s 1984, both of which have also encountered banning attempts) and gives that theme an underrepresented female perspective, which was certainly unusual in the 1980s.

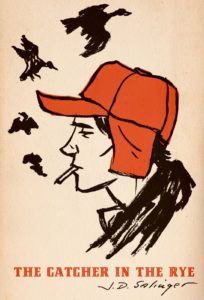

Banned for: excess vulgar language, sexual scenes, things concerning moral issues, excessive violence and anything dealing with the occult.

Banned for: excess vulgar language, sexual scenes, things concerning moral issues, excessive violence and anything dealing with the occult.

Scratch me hard enough, and, probably like many guys of my generation, I’d say J.D. Salinger’s Catcher in the Rye is my favorite book of all time. I think it’s the nostalgia. While the books was written for an earlier generation coming of age in the 1960s, Holden Caulfied spoke so well to sixteen-year-old me, disillusioned, scared, and wondering where the hell my place in the world was.

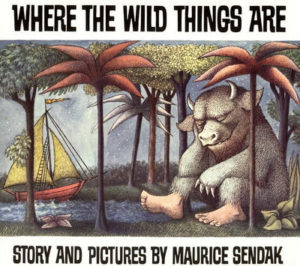

Banned for: witchcraft and supernatural elements

I always felt there was a little something subversive about Maurice Sendak’s children’s books, which was part of their appeal. I think that comes from Sendak’s point-of-view. Beneath the dreamlike wonder of his stories, there’s a minor melody of sadness and alienation, and I feel that speaks to a lot of kids.

Banned for: explicit homosexual and heterosexual situations, profanity, underage drinking and smoking, extreme moral shortcomings, child molesters, graphic pedophile situations and total lack of negative consequences

Often compared to David Sedaris (whose books have also been challenged for high school classroom reading), Augusten Burroughs writes quirky memoirs that are a little bit edgier and I’d say more affecting (I love Sedaris as well). Both the book and the movie had me in tears.

Banned for: drug use, sexually explicit acts, and obscene language

Given that parental warning, what teenager would not want to read William Burroughs’ graphic, counterculture book? Naked Lunch got passed around by my high school friends and blew open my world. Not that I’m recommending the book for early grade readers, but Burroughs’ psychodelic, polymorphously perverse rant against conformity was a wonderful affirmation of queerness that helped me better understand the world.