Many excellent viewpoints on Orlando have come out since the tragedy yesterday, many of them written by people more eloquent and insightful than me. I need to write about this, but I’ll keep it brief.

A colleague shared an article that especially propelled me to write this. It was a list of tips for allies and spoke to the importance of sharing sadness, outrage, love, and solidarity on social media, because when you don’t, those affected see that too. If this post might help one person who lost someone they loved, or anyone who feels shattered and afraid, it will have been worth doing.

Yesterday, I felt brutalized. My sense of the world as a generally safe and predictable place was stripped away, and like most of us in the new normal of gun violence and terrorism, it wasn’t the first time. I live in New York City where the sound of police and ambulance sirens are commonplace. Yesterday, every siren pricked up my defenses and paranoia. I even worried about the dangers of venturing out for my commute to work the next day.

Orlando had a deeper impact on me than 9/11 and the more recent terrorism in Paris, which is not to say that those events did not frighten me and make me cry for the victims. The difference was that Orlando was an attack on an LGBT institution, and I’m a gay man.

I grew up in fear of violence. I was bullied in junior high for being effeminate, had my property vandalized, and listened to hatred and faggot jokes and threats throughout my life. For about two decades, I watched the media debate whether or not people like me deserved the right to live our lives or even to exist in the United States. On balance, I’ve had it better than many LGBTs, due in part to my privilege as a white, middle class, cisgender guy.

Still, one of the first thoughts that occurred to me yesterday was: haven’t we been brutalized enough?

To me, Orlando felt more similar to Charleston. The difference may be hard for non-gay or non-Black people to understand. But when individuals succeed in carrying out the hate that simmers just below the surface of so many people on a daily basis, the terror carves us deeper. We hear it in the rhetoric of political leaders and religious leaders. We see it in the faces and reactions of people we encounter everyday. Orlando and Charleston are frightening reminders that hatred can come unbottled at any moment and strike us down in a hail of bullets.

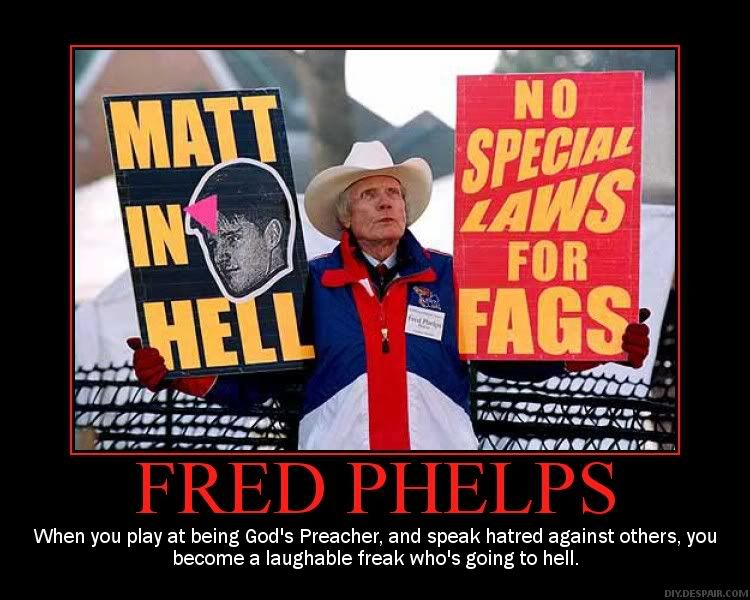

I chose the three images above about Orlando with a purpose. None of them are more or less important than any other. They are equally vital to be addressed.

We need to condemn terrorism, bring its perpetrators to justice, and strive for non-violent solutions. Further, foreign policy must recognize the legacy of exploitation that has contributed to destabilization and powerlessness, an environment where radicalization and desperation thrive.

We must speak out about the humanity, ‘deservedness,’ and vulnerability of LGBT people, inclusive of LGBTs of color. We must stand against all forms of transphobia, homophobia and racism, whether they are based on political ideology, individual beliefs, or so-called faith. Believing in a punishing, hateful god does not make your condemnation righteous. It makes you a punishing, hateful person who needs to get his head on straight if you want to live in a pluralistic society.

We need sane gun control policies. There is no reason why anyone outside of the military or law enforcement should own assault rifles.

I realize those three images and messages still oversimplify the meanings of what happened in Orlando, as well as Charleston, Boston, and elsewhere. Another issue is mental health and others may be illuminated in the days to come.

For now, I needed to say that I cannot fathom what the LGBT community is going through in Orlando, but I’m with you all the way.

If you’d like to support the victims and their families, Equality Florida has created a GoFundMe project that has happily raised nearly $3 million dollars at the time of this post.