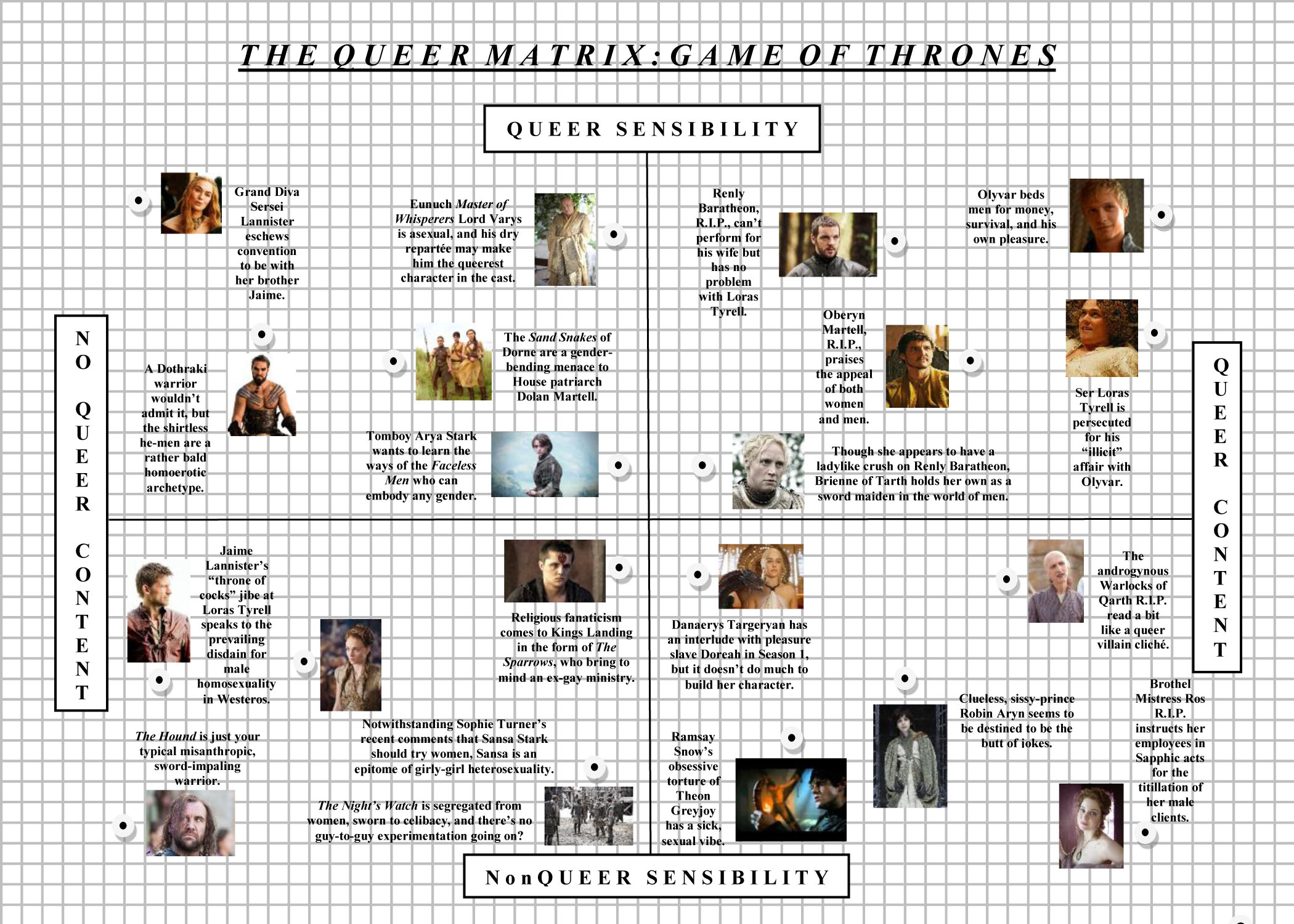

For Pride month, I thought I’d bring back a feature I created some years back. I set it aside for a long while, but you can check out my past matrices on Broadway and popular culture in the 1980s, the 1990s, and the New Millennium as well as my original post on what inspired me to create it.

So what is the Queer Matrix? It’s an analysis of popular culture along the dimensions of queer sensibility and queer content.

I define queer sensibility as a way of looking at the world based on the shared experience of queerness. Some common characteristics are an outsider point-of-view, an unapologetic belief that queer is beautiful, and the subversion of heterocentric, ciscentric, and gender-normative narratives. To say that a queer sensibility exists does not mean that every queer person in the universe has the same attitudes and perspectives. But it does avow that queerness creates distinct cultural constructs and aesthetics.

Am I being too academic? I’ll try not to turn this into a college thesis project.

Queer content is easier to explain. It is queer representations in our culture, whether literature, art, film, music or television. Queer content is explicit. It is gay sex on the page, and lesbian romance in the lyrics, and gender-bending in the visual arts.

The Queer Matrix endeavors to illustrate my belief that not all queer content reflects a queer sensibility. Furthermore, some non-queer content can be said to reflect a queer sensibility. I call the antithesis to queer sensibility: non-queer sensibility, which is the mainstream, heterocentric, cis-centric, gender-conforming point-of-view. One example of taking queer content and making it non-queer is the plethora of comedies that play around with gay situations for laughs (see: The Wayan Brothers franchise).

I am a huge fan of Game of Thrones and doing a queer matrix on the show had been bouncing around my head for a while. Before we get to that, here are some disclaimers to reduce the potential flaming I will receive. Both the topic of Game of Thrones and the topic of queer sensibility have a tendency to evoke passionate opinions.

Disclaimer #1: My queer matrix is adapted from New York Magazine’s Approval Matrix, and in the same vein: “a deliberately oversimplified guide to who falls where” on the queerness hierarchy.

Disclaimer #2: I cobble together the queer matrix by working in Word and converting the file to a jpg. Hopefully the result is passable.

Disclaimer #3: I haven’t read the books, so the matrix is entirely related to the HBO adaptation.

Disclaimer #4: If you want to pay me to do a queer matrix on your favorite topic, I won’t take money but I will happily accept your appreciation in the form of buying one of my books. 🙂

Here it is! It’s a lot easier to look at if you open it in a new tab.

And now, the discussion…

Is GoT the queerest show on television as Flavorwire pronounced a few years back? I’m not sure since I don’t watch a lot of TV, but I suspect it’s in the running, and that’s one of the reasons why I love it.

Though I’d argue that the reason GoT’s may be the queerest is not so much because of the quantity of its queer content but because of its queer sensibility.

Queer content can take several forms: sexual, romantic or gender-bending; and when it comes to the first two categories, there’s actually not a lot, despite all of the attention GoT has received for its graphic and catholic portrayal of sexuality. One, short-lived, minor point-of-view character (Renly Baratheon) has a boyfriend, and two non-point-of-view characters (Loras Tyrell and Olyvar) are shown on screen having sex with men. One minor point-of-view character (Oberyn Martell) is a proud and quite active bisexual. All four of those are men. That probably works out to one or two percent of the gargantuan cast over six seasons, and two of those guys are now dead. More about that later.

One point here is there are zero principal queer relationships that span the seasons on GoT. All of the enduring romantic storylines are heterosexual. Danaerys Targeryean falls in love with Drogo and later seems to be in love with Daario Naharis. Sersei and Jaime Lannister maintain their forbidden love affair throughout the saga. Samsan Tarly and Gilly are the couple that most people root for.

The only queer sexual/romantic content between female characters is a minor lesbian dalliance for point-of-view character Danaerys Targaryen, and a handful of instructional or orgiastic scenes involving whores in Kings Landing. That’s an even more stark disparity (pun intended).

Another disclaimer: at the time of publishing this post, season six, episode seven just came out, in which we learned that Yara Greyjoy is interested in women. That was a welcome addition to the show.

On the other hand, a lot of gender-bending goes on in GoT, particularly among the women. Point-of-view characters Breanne of Tarth and Arya Stark would rather dress in armor and trousers and wield swords than wear make-up and dresses and hope to marry well. The Sand Sisters of Dorne and Yara Greyjoy are two more examples.

So, in contrast to representations of sex and romance, queer female characters, with respect to gender non-conformity, tend to be treated more seriously and more kindly than GoT’s effeminate male characters. Mama’s boy Robin Aryn is a deranged lad who is practically comic relief. The androgynous, vampiric Warlocks meet a righteous, painful end at the hands of Danaerys and her dragons. I’m not saying that strident homophobia doesn’t fit the world of GoT, but it can make for queer portrayals that are unlikeable and reinforce a belief in inferiority, if not pathology.

Tangent: Something that became clearer to me while I was doing this matrix is that things get queerer as you go farther south in Westeros, with its southernmost point Dorne being an oasis of pansexuality and gender-bending. Most of the queer content happens in King’s Landing, Dorne and (presumably) Highgarden.

I noted the queer characters who have died (R.I.P.) as a nod to the debate over whether GoT is guilty of the “bury your gays” trope. It’s true that all sorts of characters meet untimely ends in the series. Some of them were beloved like Eddard Stark and Robb Stark (and we all thought Jon Snow), and some of them we couldn’t wait to be killed off like Joffrey Baratheon. By quantity, more have been heterosexual than queer.

What I’d say though is that when you have only a handful of queer characters and most of them get killed, the writing is slipping off the tightrope into the gay burial ground cliché. It’s hard to imagine anything good will come to the remaining gay characters Loras Tyrell and Olyvar. Both have been written into the margins of the story in any case.

Still, it’s hard for me to criticize GoT too harshly. It’s written primarily as a story of the trials and triumphs of heterosexual, cis-gender people, but I do feel it’s been groundbreaking in terms of its handling of gender and, to a lesser extent, sexuality.

I think its greatest success in those areas has been portraying women as having power and agency. In some cases that occurs through using the tools they have in the world of men, such as seduction, wisdom, or mysticism (i.e. Sersei Lannister, Melisandre, Margaeray Tyrell, and Lady Olenna Queen of Thorns). In some cases, it’s through holding their own in ferocity and martial combat (i.e. Breanne, Arya, and Yara). Danaerys is a unique example, I feel, in that she establishes herself as a force to be reckoned with through a combination of ambition, supernatural powers and a strong sense of justice via liberating the enslaved.

If The Known World held a popular election on who should take The Iron Throne, it’s pretty apparent that Danaerys would win handily. And that says a lot about the writers’ attitudes toward gender.

Banned for: excess vulgar language, sexual scenes, things concerning moral issues, excessive violence and anything dealing with the occult.

Banned for: excess vulgar language, sexual scenes, things concerning moral issues, excessive violence and anything dealing with the occult.