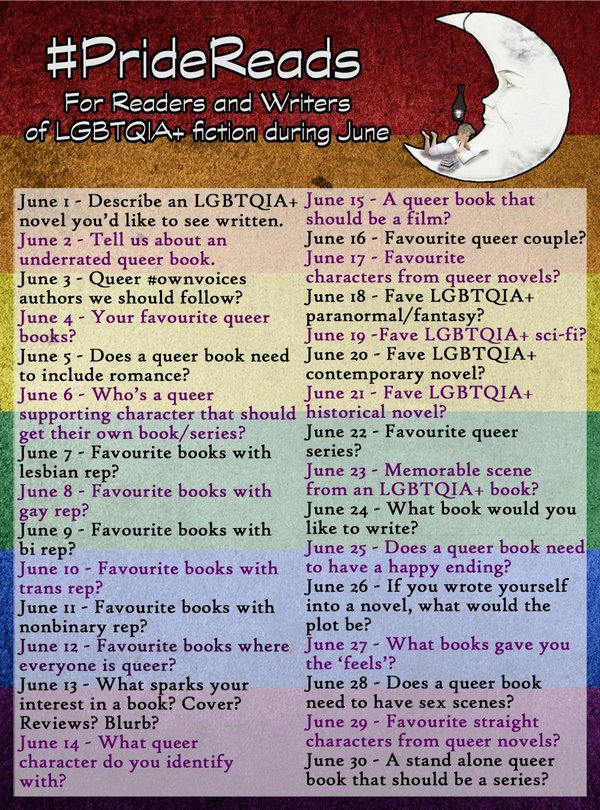

I’ve caught the Twitter hastag bug again, and this is a really good one. For June, which of course is Pride Month, the #PrideReads meme is trending to bring attention to queer books and authors. While I’m participating on Twitter, I thought I’d share some of my responses here. There are links to Goodreads in case you want to check out my recommendations.

Describe an LGBTQIA+ novel you’d like to see written?

That pretty much describes my own writing process, but I’ll pick something outside of my wheelhouse. I love historical fiction, so I’d love to read a novel featuring LGBTQIA+ lead characters set in an evocative and underrepresented setting, like say pre-colonial Mesoamerica, or Mogul-era India, or Qing dynasty China.

Tell us about an underrated queer book.

I’ll give you three. First, John Weir’s The Irreversible Decline of Eddie Socket, which is like The Catcher in the Rye set in New York City during the height of the AIDS epidemic. Second, Ben Neihart’s Hey Joe, which was awesome, modern gay YA before awesome, modern gay YA became a thing. Third, only because I read it most recently, and it’s also underrated, being far ahead of it’s time in terms of modern, matter-of-fact gay portrayals, Philip Ridley’s In the Eyes of Mr. Fury.

Queer #ownvoices authors we should follow.

@ScareBearDan @lawrenceschimel @alexharrowSFF @jscoatsworth @jp_howardpoet @Xtianbaines @johncopenhaver @JoeOJazzMoon @allanbrocka @AnnAptaker @TrustMiguel @Hans_Hirshi @BrianCentron @CAClemmings @KenJONeill & sorry I ran out of characters

Your favorite queer books.

[Head explodes] Well gosh, here I’ll stick to my wheelhouse to put some boundaries on it. For SFF #Ownvoices, Samuel Delaney’s Tales of Neveryon, Ricardo Pinto’s Stone Dance of the Chameleon trilogy, and Douglas Clegg’s Mordred, Bastard Son are probably my favorites.

Does a queer book need to include romance?

Absolutely not, though my reading “sweet spot” is action-adventure with a minor romantic storyline that doesn’t have to be HEA.

Who’s a queer supporting character that should get their own book/series.

I’m going to go off canon because I didn’t read the books (shame, shame, shame), and I understand the character of Olyvar in Game of Thrones was created for the TV series. Anyway, he’s my favorite gay character in the series (and the only one who hasn’t been killed off!), so my vote is for Olyvar to get a platform to do some damage in Westeros.

Favourite books with lesbian rep?

I really liked Malinda Lo’s Ash. Also, though not an #Ownvoices title, Richard Morgan’s The Steel Remains has a well-developed lesbian character Archeth who I thought shone through as the best POV character.

Favourite books with gay rep?

I mentioned a bunch of them above, but this gives me a chance to share more! For literary/history, I’ll shout out Felice Picano’s Like People in History. For mystery, Michael Nava’s The Burning Plain is probably my favorite title from his Henry Rios series. For family saga/coming of age, Shyam Selvadurai’s Cinnamon Gardens. For YA, anything by David Levithan. For romance (guilty pleasure), Scott Pomfret’s Hot Sauce. Last, for humor, far, far off the radar: Andrew Killeen’s The Khalifah’s Mirror and Jim Anderson’s Chipman’s African Adventure.

Favourite books with bi rep?

Going to do a throwback here, I read Hanif Kureishi’s The Buddha of Suburbia as a young adult, and it’s one of those books that stayed with me for years and years.

Favourite books with trans rep?

I haven’t read nearly as many trans books as I should have, and the book I’m going to mention probably fits better as intersex. But Jeffrey Eugenides Middlesex is a terrific cultural and historical saga in which the main character was born with ambiguous genitalia and lives as a girl and a young man and later as someone in-between.

Favourite books with non-binary rep?

Here again I’m shamefully poorly-read, and to mention Ursual Le Guin’s The Left Hand of Darkness feels somewhat lame, since so many books about trans and non-binary experiences have been written since that groundbreaking SFF came out. But there I did it. I’ll add Daniel Heath Justice’s The Way of Thorn and Thunder, which takes inspiration from Indigenous lore and traditions, including non-binary ways of living.

Favourite books where everyone is queer?

I love this question because I think it’s an underrated approach to queer fiction, and it’s not uncommon to see reviews of queer books that complain it’s “unrealistic” there are so few straight characters (barf). So here’s to Alex Sanchez’ Rainbow Boys series with three rotating gay male narratives and Allison Moon’s all-lesbian Lunatic Fringe, and Matthew Rettemund’s Boy Culture, and all the fabulous queerly retold fairy tale collections like Lawrence Schimmel’s The Drag Queen of Elfland and Jeremy McAteer’s Queer Tales: Fairytales for Gay Guys.

What queer character do you identify with?

As a closeted queer teen, I devoured Paul T. Roger’s Saul’s Book, and thought I found in the narrator Stephen a deeper understanding of myself. Later, I’d say I saw more of myself in Duncan from David Levithan’s Wide Awake, with his heartfelt conviction in social justice. Nowadays, with a dearth of stories featuring older queer characters, the one who comes to mind is Gabriel Noone from Armistead Maupin’s The Night Listener.

What sparks your interest in a book? Cover? Reviews? Blurb?

This is an interesting question in the context of queer books, because thinking back to my coming of age in the 80s and 90s, living in upstate New York, it was hard as hell to find the kind of books I was interested in! I pretty much had to sneak into the stacks at librarires or bookstores and find the sexuality section, which felt like a huge taboo in itself. Even then, I had to find titles catalogued with the sterile, scientific label: homosexuality and hope they weren’t insidious, pseudo-scientific, neo-Freudian, pathologizing horseshit.

The covers of those older books rarely gave hints about the story, and the books were all fairly tragic, violent and highly sexualized (not a bad thing necessarily, especially for the young, disaffected me who was also quite eager to learn what gay men did together).

With the advent of the Internet, it became a whole lot easier to find queer books I might like. Covers matter to me, though looking through my Goodreads shelf, some of my favorite titles have pretty awful ones and that doesn’t stop me from singing their praises. I read blurbs to see what the story is about, and I’ll check out what people have to say on fan sites and Goodreads.

Favourite queer couple?

I often say my favorite couple is Gorgik and Little Sarg from Samuel Delaney’s Tales of Neveryon. They lead a frickin’ slave rebellion that liberates an entire country, so try beating that. Honorable mentions: Maurice and Scudder in E.M. Forster’s Maurice (I weep at the end of the movie), and though the relationship is muted and ill-fated in Gregory Maguire’s inimitable way, I loved Liir and Commander Cherrystone in Son of a Witch.

Does a queer book have to have a happy ending?

That’s a provocative and important issue to talk about. I expect a lot of readers would say we need more queer lit with happy endings to balance out the long history of tragic queer stories–those classics like Lillian Helman’s The Children’s Hour and Thomas Mann’s Death in Venice, which suggested the impossibility of queer people finding love and leading happy, well-adjusted lives.

Some of those books, now called “bury your gays” tropes, were written from a non-queer point-of-view, which is susceptible to marginalizing, tragedizing, and at its worst demonizing queer people, e,g, the tendency to portray villainous characters as sexually ambiguous as a foil to the heteronormative hero/heroine. Yet some queer tragedies of the past were written by queer people themselves, like James Baldwin, Manuel Puig (Kiss of the Spider Woman), the aforementioned Lillian Hellman, Patricia Highsmith, and you could say most of the authors known as The Violet Quill who broke ground with realistic portraits of gay men living in the 1970s and 1980s (Edmund White, Andrew Holleran, and others).

Themes of death and suffering reflected salient aspects of real life for queer people, and I’d say writing about those issues was both realistic and helpful for readers, both queer and straight, to better understand the challenges faced by queer individuals (and for queer readers, to realize they’re not alone with their personal struggles).

All of this is to say I subscribe to the notion embodied in a famous quote by Ernest Hemingway: “A writer’s job is to tell the truth.” And the truth is some queer lives are tragic, some are triumphant, and all of them are filled with many moments of both. So no, a queer book doesn’t have to have a happy ending. But I would hope there’d be at least an equal number of books with happy endings as books that end tragically. And then, of course, stories are more complex than happy vs. sad. I tend to enjoy books that take me on a journey that runs the gamut of emotions.

Does a queer book have to have sex scenes?

Here’s another question that on its face sounds simple.

No. Why in heaven’s name would a queer book have to include explicit sex? There are tons of ways to write about queer people that don’t involve what they like to do to get it on.

So yeah, I enjoy all kinds of queer stories that have no sex or very little sex, and I certainly don’t feel as a writer that I need to add a sex scene in order to develop a queer character or make the story more interesting or marketable.

But as a guy who’s always been much more interested in queer liberation versus assimilation, I also feel it’s important to add that queer sex scenes can be marvelous and subversive and fabulously declarative and rebellious. Writing queer sex is a political act, and I respect writers who do it and think it’s important that it has a place in our literature.