Hey folks! Continuing with my retold myth project for 2018, I’m posting my next recently completed story: “Telemachus and His Mother’s Suitors.”

I remember reading The Odyssey in high school and being much more enchanted and engrossed than I had been with its partner required text The Iliad. I liked The Iliad for its style and language, the interplay between gods and mortals, and some bits of drama (the Achilles vs. Agamemnon storyline stayed with me the most). But you’ve got to admit: the battle scene passages of “he smote him, and he smote him…” go on and on and are mind-numbing. For me, they kind of took away from the more interesting dynamics between the characters.

Sorry Homer. Everyone’s a critic, right?

The Odyssey on the other hand struck me as a more imaginative, full-fledged adventure. I didn’t even need the Cliff Notes to participate in class discussion or write my paper about it. The story had me glued. I’ve often thought of characters and storylines that would be fun to slash, subvert and reboot, though this is the first time I put fingers to keyboard to do it.

Margaret Atwood wrote a fine re-telling from Penelope’s point-of-view with the Penelopiad, and I suppose I can trace my interest in Telemachus from there. In the original story, Telemachus is a rather impossibly virtuous, ever-loyal son, who scours the world, risks his life to find his absent father. That’s sweet, I guess, but I never really bought it. Atwood gives Telemachus a bit more humanity, though she still portrays him as fiercely loyal to Odysseus, and I found her version, while intentionally and admirably centered on Penelope, who was very much in need of more dimension, at the same time somewhat neglectful of the inner life and motivations of her son.

So here is what I re-imagined for Telemachus. It’s not much more than a brief portrait. Who knows. One day I might take it further.

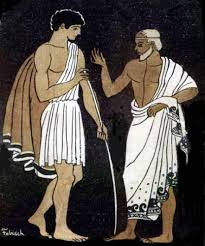

Pablo E. Fabisch, illustration for Aventuras de Telémaco by François Fénelon, retrieved from Wikipedia Commons

They had overtaken the parlors, overtaken the courtyard, even overtaken the larder Telemachus discovered when he went to fetch a jar of pickled fish to serve the rowdy guests. Stumbling at the portal to the storeroom, he found instead the backside of one of the men. The gentleman’s tunic was unfastened from his shoulder, pooled around his ankles, and he was plunging between the pale and outstretched legs of a girl Telemachus gradually recognized as one of his mother’s laundrymaids. He stood wooden, afraid to make a sound, eyes widening from the sight of the man’s thick and hairy thighs, his starkly bare bottom, his urgent, rutting motions. Then he turned around very quickly and scurried the other way with his head bowed to hide the flush on his face.

The men were beasts, as gluttonous as swine, as horny as the dogs who skirred along the roadway to town, noses to the ground, sniffing out some opportunity. And they were brash and loud and foul-mouthed, and, young Telemachus hated to admit, they were woefully appealing with their clothes undraped while they staggered through the hallways and lay across every bench, divan, and table in the house. He tried to avert his gaze from bare chests, hardened arms, roguishly handsome faces. Some of the men had even thrown up the skirting of their robes to dance around like woodland satyrs.

It was a feast for his eyes, yet a terrible affliction. What kind of man was he, to desire his enemy? They had pushed into the house with no regard for its owners, and if he were not so girlish, he would do something about it. His mother had locked herself up in her bedroom. By right, Telemachus was master of the house. He knew he should protect his family’s honor, to stand up for himself for that matter. But he shrank from the thought of challenging the men, rousing a fight. He was one, a youth of nineteen years, whose awkward tries to raise his fists, heft a sword for martial training had exhausted his tutors’ patience and drawn laughter from his peers. The guests were dozens, some of them soldiers, some twice his age, some twice his size. Who would heed his command?

This was his father’s doing, or was it his own? Telemachus could not say, and it left him feeling as useless as a skittish cat. All he could think to do was to appease the guests and hope they would leave him be.

Grasping for some purpose, he went to the cellar to drag up another amphorae of wine. There was no one else to do it. The servants had abandoned the house with the exception of some of the maids, and those that remained were carousing with the guests, sitting on their laps, laughing while the men nuzzled at their breasts, and playing games of chase around the courtyard. No, he was not even as consequential as a skittish cat. He was a ghost amid a party to which he had not been invited.

His grandfather had foreseen his inadequacy. He had told his mother: Without a father, how is he supposed to grow into a man? This, when Telemachus was just a child, and before Laertes fell ill, unable to become a surrogate for an absent father. His father had sailed off to the war in Troy when Telemachus was just a baby. That had been nearly twenty years ago. Already, three years past, the first warship had returned to harbor hailing the victory of the Achaean alliance, yet his father had never returned.

They had said Odysseus survived the battle. Two men avowed he had been among them when they celebrated the sack of Troy with a great victory feast. Odysseus the Wise, they had called him. They had said his father had conceived the strategy which had led the Achaeans to victory.

At the time, the soldiers had beseeched his mother not to despair. The voyage home had been difficult. Angered by the defeat of the Trojans, mighty Poseidon had beset their ships with rail of wind and waves. Could be Odysseus had been forced to make harbor along the way, awaiting gentler conditions to try the sea again.

His mother had not despaired, but they both knew three years was an awfully long time to wait to make a journey home. Sometimes, Telemachus wondered if word of him had travelled to his father, and he had decided to make a family elsewhere due to the shame of him. He wasn’t wise, nor brave, nor strong, nor skilled in military arts. He certainly was not fit to be king of Ithaca, and meanwhile the country needed a king.

Two big jugs of wine, the height of Telemachus’ chest, were left in the cellar. Telemachus heaved and dragged one of them up the stairs to the kitchen and hunched over himself to catch his breath. The floorboards were gritty with dirt. They had been unswept for days. Everything was in disarray—vegetable peels strewn on the counter, piles of plates and cups in the wash basin, cupboards thrown open revealing bare shelves. It was a terrifying situation when Telemachus thought about it, so he tried not to. What would happen when all the food was eaten and the last amphorae of wine had been drank?

Straining his legs and his back, he hefted the wine jug into the clamor of the courtyard. The men spotted him and raised their voices in a hearty cheer. Telemachus turned his face from them, smiled and blushed. Well, he could not help but be enchanted by that nod to him belonging in their fraternity.

One of the guests stood up from his stool and swaggered toward him. Telemachus tensed up, expecting trouble, and equally abashed by the sight of him. The man was only clad in a tunic skirted around his waist. Telemachus tried not to look upon him directly, but his damnable eyes were always thirsty. The fellow was admirably built, in the prime of manhood. Broad-shouldered. Brown-berry nipples. A thatch of curled hair in the cleft of his chest. The man’s face was a further delicious horror: square-jawed, probing, dark-browed eyes, an auburn beard flecked with gold, and a rakish smirk. Telemachus was excruciatingly aware of the courtyard quieting and attention fixing on him, the queen’s son.

The man clasped his shoulder in a brotherly way. His big, warm hand sent a melting sensation through Telemachus’ body. He pried out a square look from Telemachus, and he winked at him. Then he brought out a coring knife from a leather holster strapped around his thigh and helped uncork the jug so the men could refill their goblets.

A glimmer of mirth passed over the man’s face, and he looked out to the courtyard. “If we cannot have the queen, perhaps we should have her son?” He whopped Telemachus on the bottom with the outstretched palm of his hand, sending Telemachus teetering, nearly doubling over himself.

The courtyard brayed with laughter. The man wriggled his eyebrows at Telemachus and strode back to his companions. Telemachus stole into a darkened corner of the courtyard, burning even hotter in the face. The sparks from the man’s wallop lingered, and he was stiff between the legs. He discreetly fanned the skirting of his princely chiton, shifted his weight, trying to relieve that painful ache before anyone caught a glimpse of it.

When it was gone, he drew up to a spot where he could see his mother’s bedroom. A single house guard was posted at the door, scowling at the commotion below. The man had been employed since before Telemachus had been born and would lay down his life to protect his mother, but he had grayed and turned soft-bodied. He was hardly a barrier if the guests decided to storm the queen’s quarters. Every other house guard had run off in a mutiny, likely corrupted by the men who had invaded the house. The men’s commotion felt charged, ready to explode with violence.

Telemachus snuck up the stairs to have a word with his mother.

~

The shutters had been drawn in his mother’s bedroom, perhaps to drown out the noise below. It was not a particularly cool, late summer evening, and the room was musty. She had lit a pedestal of candles on the table nearest to her bed, and it filled one corner of the room with a warm, fiery glow. Telemachus swam through a lacuna of darkness to her bedside. Her room was drenched in a pleasant lavender scent. Telemachus would always associate that fragrance with his mother, an olfactory memory of comfort and confession.

She was bedded with a funereal shroud on her lap, staring at the woven fabric as though it held wise secrets to decipher. She had finished the shroud one week ago, a pretext for putting off her marriage.

After a year of his father’s absence, the elder council of Ithaca had appealed to his mother, saying it was time Odysseus was declared dead, or—what most had judged—delinquent. Every Ithacan soldier had returned from Troy, whether on his own two feet or on a funeral bier. Ithaca needed a king thus Penelope must marry. In worldly cities like Athens, where free men voted as one body, they had even established laws to permit remarriage after a year of husbandly abandonment.

Penelope was not a woman who bowed to the opinions of councilors, however. She had announced she would not entertain any offer of matrimony until she had finished the shroud for her father-in-law Laertes, who was not long for the world. Meanwhile, she had ripped apart her progress each evening to start anew. By providence, Laertes had held on for years. Not so Penelope’s scheme. They knew not who had revealed the truth. Her body servant? A spiteful maid? Well, it did not matter. The ruse was over, and now their house was under siege by every man of marriageable age across the island.

Telemachus stood beside his mother for a moment before she turned to him as though suddenly awakened to his presence. She smiled at him in her easy manner. They said she was not beautiful like his aunt Helen who had roused the world to war, but she was beautiful to Telemachus. And when she looked at him so warmly, so proudly, he felt beautiful too. She reached out to touch his arm and patted the bed, inviting him to sit.

She read the worry on his face. “What is it, little lamb?” He sat down, faced away from her. They could hold no secrets from one another, even in silence, and what worried him was hard to say.

“How long will you hide yourself?”

It came out harsh, accusatory. She sat up, took his arm, pulled him gently toward her, but he resisted. Her lavender scent, mixed with the smell of her worn bedsheets, surrounded him.

“You have to choose,” he said.

She leaned against him, her face above his shoulder, trying to nudge out his gaze. Not succeeding, she picked at the ends of his wavy, flaxen hair. “Must I, little lamb? Would that you had been born a girl. Then we’d simply marry you off and have a prince-in-waiting to succeed the widowed queen.”

He shrugged away from her.

She laughed. He knew she had not meant to mock him. His mother was never cruel in that way. Teasing and bossy, perhaps, but never cruel. They only had each other in the world.

But she needed to act. The horde of men below them would only contain themselves for so long. Their hollers and bawdy chatter carried through the house, and some of them had risen up in a chorus, calling out his mother’s name.

Her warm hand clasped his arm. “Who would you choose for me?” she said. “A handsome man like Antinous, the horse-trainer? A wealthy man like Amphinomous, who owns the shipyard? Or Eurymachus, a man more like your father, always tinkering with his gadgets and playing at being a philosopher?”

Telemachus grinned in spite of himself. If it were he entertaining suitors, he would choose the auburn bearded man who had slapped his bottom. His skin was still alive from the man’s touch, and he was quickly blushing again. But a son did not choose his mother’s husband.

He scolded her, “This is not a game.”

“It is precisely a game,” she insisted. “Do you believe each one of those men downstairs has been stricken by my beauty and come to win my heart? No, they’ve come for my father’s dowry. What little is left of it. Or, they’ve come for the power to rule. For kingship of Ithaca. Of which they will be similarly disappointed.”

Their farmland had been untilled for months. The house was starting to look a shamble, and in terms of country, Telemachus followed somewhat. Ithaca counted for little in the world, particularly now that the war was over, and the Achaeans had returned to their tribal states. Men sought greater fortunes on the mainland: Sparta, Corinth, Thebes. Ithaca was an island of fishermen and peasants.

“I’ve had enough of marriage,” she went on. “One year was plenty.”

He turned to her and scowled.

She eased up beside him, held his shoulder. “Do not be moody. You know I would not have traded being your mother for all the riches in the world. But if I had had to live with Odysseus all these years…” She shivered from the thought and came back to Telemachus again. “I believe your father and I had the perfect marriage. Men and women should not be forced to live together for longer than a year. I think I shall suggest that to the elder council. A new statute for Ithaca: every husband must be sent to war no more than one year after the consummation of his nuptials.” She laughed. “What do you think of that?”

He frowned. His mother was so strange. She hadn’t a romantic notion in her head. Did not people fall in love? It was said his aunt Helen had. She ran off to another country to be with the man she loved, rather than settle on a marriage to the man her father favored. His mother told that story as though her sister had done a very foolish thing, as everyone in the world did foolish things in her estimation. But it used to keep Telemachus up at night imagining golden-haired Paris, wondering if a man like him would ever steal him away to a faraway kingdom.

“I see I have not convinced you,” she said. She sat up, smoothed out her smock. “Well then. Do you want another father?”

He shook his head.

“Good. It’s settled. No husband for me. No father for you. We run wild, as cats.” She smiled, glanced at him, contrived a more serious look. “Though I shall not stand in the way if you should like to marry. You’ve nineteen years. A respectable age. Should you like me to start looking for your wife?”

He gaped at her. “No.”

“Splendid,” she proclaimed. “Then we shan’t ever have to send you away to war.” She took his hand, squeezed it. “That makes me the luckiest mother in the world. To have a son who will never leave her.”

He squeezed her hand back. He had not thought of leaving her, in any practical way. Though a man does leave his mother someday, doesn’t he? Gray thoughts returned to him. “What will you do?”

She took on a playful air. “What shall I do?” she repeated. “Enact a contest to win my hand? What do you think? A round-robin bout to the death?”

He smirked at her reproachfully.

“Too gory? Well then…” An idea flashed in her eyes. “I do love an archery contest. And it is said an archer has the soul of the centaur. Always wanting the freedom to roam. Never setting down roots.” She sat up straighter, gaining inspiration. “Let us enact a challenge. Have we still your father’s axes in the backhouse? The ones with eyes on their heads?”

Yes, he remembered seeing them. There were twelve ornamental axes hung up on one wall, some dusty collection that must have passed down to his father. They had never been used.

“Let us set them up, eye to eye, and see who can send his arrow true through all of them.”

Telemachus tried to picture it. “That’s impossible.”

“Oh no. I do not think so,” she said. “It is a feat that can be done by the deftest and most honorable of men. A man who has been blessed by Artemis, the mighty huntress herself. Each contestant shall get one try, and whoever succeeds can claim me, along with the throne of Ithaca.”

He scoffed and awaited her laughter. It did not come.

“In the morning,” she told him. “Go to Eumaeus, the swineherd. Tell him what I have planned and that we need wood to build a rack. He will help. For some reason, known only to the gods, he was always fond of your father.” She added: “Do not encourage Eumaeus too much. Lest we be tending pigs the rest of our lives.”

She smiled at her little jest. He wondered how he had turned out so meek, so uninspired while she was clever and fearless, and his father, by rumor at least, was wise and bold. The swineherd’s farm was down the hill from their estate. He would go to him at dawn and waste no time in getting his mother’s enterprise underway.

Telemachus sat up from the bed and nodded. Then he left his mother to spy upon her guests.

~

The men had quieted by a measure when he returned downstairs. Someone was plucking a lazy, melancholy melody on a kithara in one of the front parlors, and mad, girlish laughter traveled from another room. Telemachus nearly tripped upon a man who had laid down on the dusky side of the courtyard. Stepping around the body, he saw no blood, no injury, and he heard drowsy, nasal breaths. The fellow must have overdrunk his fill.

Telemachus breathed air into his lungs, smoothed out his chiton. If what he was to do was to be done, he could not think about it too long, allowing faintheartness to overwhelm him.

So he edged around the courtyard, taking account of a cluster of men rolling dice. The number of guests had dwindled and those who remained were heavy-shouldered, glassy-faced. He recognized Antinous, who his mother had spoken of. The fair-haired equestrian was slumped against a beam, his eyes shrunken to a squint. Some of his mates bantered around him. They were all too preoccupied, too slow from drink to notice Telemachus slip by.

A terrible thought occurred to him. Had he returned too late?

He looked in on a front parlor and quickly stole past the door. A trio of naked maids were swaying in a clumsy dance, and he had seen two, maybe three shadowed men strewn around the room, staring at the girls deliriously. Possibly, most of the guests had gone home for the night, though there were other parts of the house for Telemachus to investigate.

While he dallied, a big, brute stepped out of the water closet across the way. His gaze found Telemachus, who was temporarily stricken to stone by his discovery. The gruesome bounder looked him up and down. A wolfish grin sewed up on his face. He called out, and Telemachus got his legs moving again, hastily retreating toward the kitchen, and then crossing the way beneath the staircase where he hoped the man would not find him. He listened and peeked back to the front of the house. It seemed the man had decided not to pursue him.

Now he was sweating and felt very foolish. He ought to abandon this dangerous endeavor, go up to his bedroom and bolt the door for the night. Yet that was not the man he wanted to be, at least for once. He dried his brow with a kerchief and looked around the yard again.

Some paces away, the door was open to a bedroom which had been the quarters for the male servants before those traitors had left him and his mother to fend for themselves. The faint glow of an oil lamp spilled out to the yard. Telemachus heard low voices. He stepped lightly over to see.

A small company of men were distributed around the pallets, slumped and weary, passing around an urn of wine. They slurred a conversation, which seemed of little consequence. One fellow collapsed onto his back. The others laughed, tossed back more drink. Staring keenly, Telemachus beheld a man in one corner shaving a brick of wood with a hand knife. Light was stingy in the little chamber, but he recognized the size, the shape of his bare shoulders, his dark, romantic eye brows, the timbre of his beard.

What to do? Four other men were in the room, and if any of them should see him, they might decide to try some mischief with the queen’s son. Telemachus had spent his life steering well aloft of gangs of soldiers who doled out miseries to timid, unaccompanied members of their gender. He steeled himself and stared at the auburn bearded man, imagining him lifting his gaze and looking to the door.

The moment came. Maybe he had harkened to a displacement beyond the room or noticed a shift in lighting from the doorway. Maybe he had a preternatural sense, feeling the young man’s eyes upon him. He dropped his woodwork onto his lap and blinked. A grin bedeviled Telemachus, and he composed himself with one hand on the doorframe, fluttering his eyes as a forest nymph might beckon a handsome stranger (had he truly been so bold?). The man took a quiet account of his companions and came back to Telemachus with a question mark on his face. The prince gazed over his shoulder, raised one corner of his mouth, and then he snuck slowly down the hall.

His heart pounded in his chest. Would the man follow him? His stomach was strung up tight, and his head was so terribly scrambled, he could not tell if a footfall traveled after him or he was imagining it. Into the darkened kitchen, he heard what sounded like dragging steps behind him. What had he done? Seducing his father’s enemy? Did that not make him a traitor? Yet what loyalty did he owe Odysseus? His father had not shown loyalty to him. No, this was what he wanted, and if he did not do it now, then when?

Telemachus stepped into the larder. By grace, the storeroom was vacant. Only the disorder from its previous occupants remained: shelves topped from walls, tins and jars spilled and broken on the floor. This was the place where he would have his own tryst, and whether it blossomed into a love affair that would change his life forever or counted as no more than a stolen moment of happiness, well, so be it.

He turned back to the portal and set his eyes on a dusky silhouette in the door frame. The man stood still for an excruciating moment, and then he closed in on Telemachus. Their mouths found one another, and they tore at each other’s clothes.

# # #

If there’s a classic myth you’d like me to try my hand at, let me know! You can also pick up my story “Theseus and the Minotaur” at Smashwords.