Hi. It’s me again. The guy who posts every now and then, letting weekly deadlines go by, and feeling less and less guilty about it.

The functional breakdown I predicted last semester has arrived, and my beloved blog has been the worst victim of my negligence.

Elsewhere, I really have been doing a lot of productive things. An idea for an urban fantasy has turned into a 10K and growing story (novella?). I organized an LGBT writers critique group, which has taken off marvelously.

But this blog has been my rock throughout the ups and downs of my writing life, and it’s time to get back to it. Sorry rock :::rubs cute little rocky head:::

Thus, I retake to the blogosphere with some words on what I’ve been reading.

Despite my quibbles with Nick Drake’s first book NEFERTITI: THE BOOK OF THE DEAD, I picked up the sequel TUTANKHAMEN: THE BOOK OF SHADOWS. Drake’s writing is just so extraordinary, and I love the ancient Egyptian setting.

The second book has Rahotep, a clever Medjay officer, appointed to investigate threats against the young King Tutankhamen. Tutankhamen is despised equally by his great uncle Ay, protectorate of the kingdom during the reign of the child King, and the popular military hero Horemheb who has political ambitions of his own.

Meanwhile, Rahotep is haunted by the horrifying ritual murders of a serial killer, which may have something to do with the subversive campaign against his client.

Drake renders the people and places of ancient Egypt vividly and beautifully. His prose is at times poetic, and always efficient. I thought that Tutankhamen was a particularly successful character here, shown in his complexity: pampered, naive, wounded by the murder of his father who he succeeded to the throne, and wanting to make something of himself.

More actual mystery solving happens in the story than in NEFERTITI, a complaint of mine with Drake’s début novel, and it made for some satisfying reveals. Rahotep comes to life as a man with special gifts for reasoning and deduction, truly an ancient world detective.

There’s a lot to recommend TUTANKHAMEN, and I do. But being the peevish critic that I am, two problems kept the story from lifting from “great” to “excellent” territory.

First, Rahotep’s quest – to protect Tutankhamen – didn’t feel quite profound enough to hold my fascination. Drake has done extensive research to bring ancient Egypt to life, with historical accuracy, but as such, it wasn’t clear to me what the assassination of Tutankhamen would mean to people beyond the inner circle of privileged and oppressive elite. Put differently, I didn’t get the sense that the young King would be any more effective as a leader than his despotic and corrupt rivals.

Perhaps this is the essential challenge of writing an ancient world story for modern readers. We want to be transported to a vivid ancient time and place, but there has to be something there to relate to: a universal human struggle, for instance.

My other qualm is a carry-over from my review of NEFERTITI. Rahotep’s personal conflict – sacrificing his family life in favor of his dangerous work as a detective – is peppered into the narrative through sentimental ruminations and passages of ‘home-sweet-home’ domestic life. I wanted more from the portrayal, or maybe less, or maybe something entirely different. It felt like a convenient device to make Rahotep relatable to modern readers.

Still, TUTANKHAMEN will impress fans of ancient Egypt. The story delves vividly into the worldview and religion of the time as well as the curious details of daily life.

Here’s a younger, leaner Poseidon. It’s a famous bronze statue circa 5th century BCE Greece. I bought a copy of it in Mykonos. He looks more athletic, less musclebound, in these earlier renderings.

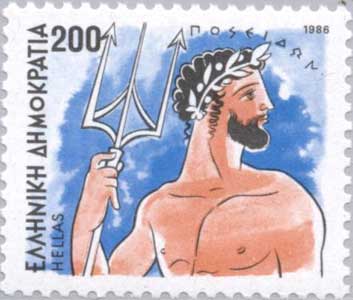

Here’s a younger, leaner Poseidon. It’s a famous bronze statue circa 5th century BCE Greece. I bought a copy of it in Mykonos. He looks more athletic, less musclebound, in these earlier renderings. Here’s Poseidon on a Greek postage stamp.

Here’s Poseidon on a Greek postage stamp. I like this illustration by artist

I like this illustration by artist