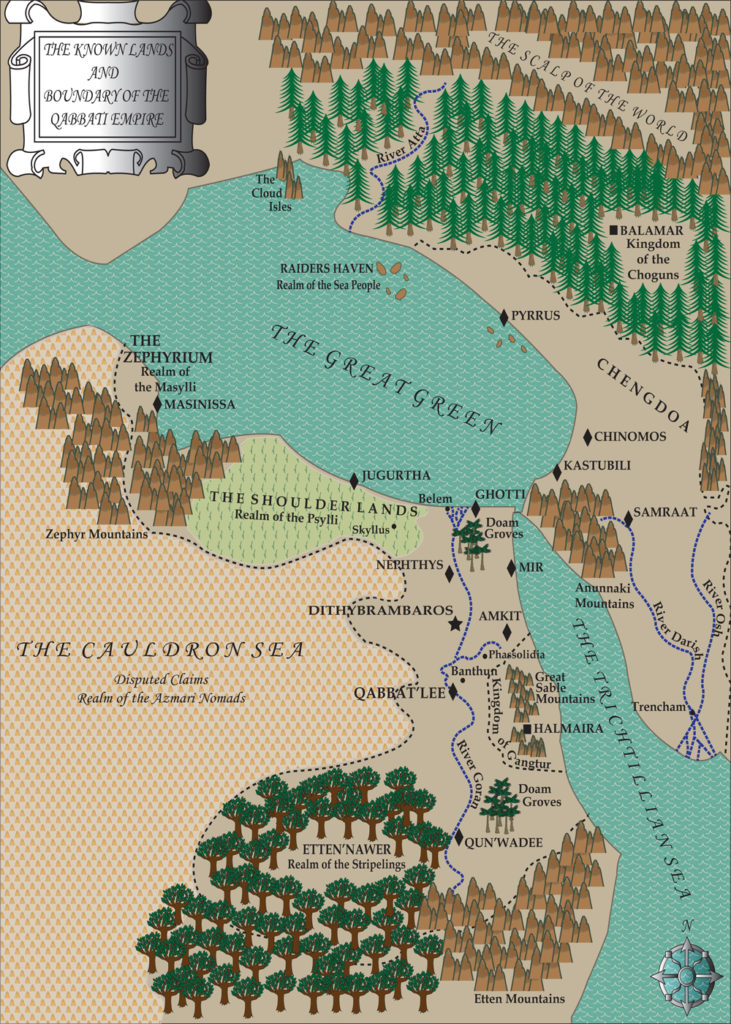

Map of The Known Lands, designed by myself and my husband Genaro Cruz

For The City of Gods release week, I thought I’d share the “story behind the story.”

So first, the story in front of the story is a turning point in two young men’s lives. Kelemun is a nineteen-year-old boy from the slums who, owing to his good looks, was bought from his parents at the age of twelve to be indoctrinated as a kouros priest in the Temple of Aknon. For Kelemun, it was grist to show his stern, disabled father he’s not a burden, and he works his way up to favored status in the priesthood. Young priests are chosen to exemplify the lord of beauty and propagation, and they tend the inner sactum of the god, which attracts pilgrims from around the world who pay fortunes to beseech Aknon for miracles.

As he has been taught, when a pilgrim wants more than to behold his golden likeness and pray with him, he provides. His body is a vessel of Aknon. But when a handsome prince of untold wealth fervently and chastely pursues him, Kelemun begins to question what he thought he knew about himself.

Ja’bar is a few years older and of a fantasy race called Stripelings, tall and broadly built with skin like molasses swirled with honey. He has known indentured servitude as well. He comes from a country where a crooked king made slaves of his own people to harvest fruit and lumber from his precious doam groves. Ja’bar broke out of the slave barracks when the emperor offered Stripelings freedom if they joined his army to overthrow the king.

After the war, having no kin to root him, Ja’bar came up north to learn about the world in the famous city of Qabbat’lee, and he was picked out from mobs of grunts to be a warden at the Temple of Aknon. Ja’bar’s not fond of working for folk who worship a god who commands that boys be used for profit, though in his experience, it’s best not to question the people who put bread in your hands. Guarding the temple is good, paying work for a Stripeling, a jungle savage in the eyes of the northerners, and a whole lot better than gambling his life on a bloodsport stage as many of his kind end up doing. He has a dream to buy a plot of river land and never have to trouble with anyone being his master. But when the high priest starts giving him jobs that are more and more ruthless, he wonders if he’ll be able to live with himself with a dream paid for by the misfortunes of others.

A chance encounter between Kelemun and Ja’bar leaves indelible impressions and the possibility of a better life for them both.

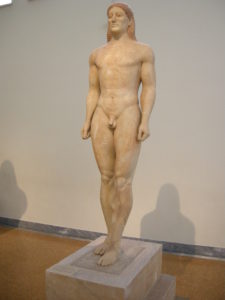

So how did I come up with this far-flung story? The first thing that interested me was exploring temple life in ancient times, and in a sense Kelemun was an expansion on the character of Dam, a young priest in The Seventh Pleiade and Banished Sons of Poseidon. The position of boys in the priesthood is fascinating to me. On one hand, it was an opportunity for learning, and room and board, in a feudal society where education and finer trades were not easy to come by.

5th century B.C.E. Kouros statue at the Museum of Archeology in Athens, retrieved from Wikipedia Commons.

On the other hand, priests of the ancient world, particularly the underlings one must assume, were not regarded with our modern sense of deference. They were more like workers, providing crafts for their communities, and the Greek historian Herodotus wrote about the practice of temple prostitution from his travels around the ancient world.

It’s impossible to say how reliable his account was (the Greeks, like the Romans, were known for disparaging the “barbaric” practices of other civilizations in contrast to their more righteous society). But it gave me the idea for a religious cult that prospers through a combination of mysticism and sex trafficking.

One thing I took liberties with was the idea of the kouros, another source of inspiration for me. Kouros iconography was an ancient practice, probably influenced by early artwork of the Egyptians and proliferating throughout Greece before the classical age.

The kouros archetype lives on in images of the young male ideal such as this ad for a cologne from Yves Saint Laurent.

The kouros was associated with the handsome god Apollo, who may have been the “gayest” of the Greek gods based on his exploits with other men (Hyacinth, who he turned into a flower after his death; Cyparissus, who became the cypress tree after their ill-fated affair; and Iapyx, who Apollo gave the gift of healing, among others). I was curious about the possibilities for an ancient religious cult that worshipped a male god of beauty via priests who emulated his likeness. Thus Apollo became the more Egyptian “Aknon.”

Here’s part of a paean to Apollo by the 3rd c. B.C.E. poet Callimachus:

So, young men, prepare yourselves for singing and dancing.

Apollo appears not to all, only to the good.

He who sees him is great; who does not is lowly.

We will see you, Worker from Afar, and we will never be lowly.

Let the cithara not be silent.

Nor your step noiseless with Apollo approaching, you children,

If you intend to complete the marriage vows and to cut your hair,

And if the wall is to stand on its aging foundations.

Well done the youths; the strings are no longer at rest.

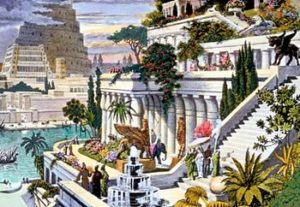

A 19th century rendition of the Hanging Gardens of Babylon, image retrieved from Wikipedia Commons

Another point of inspiration was the great cities of the ancient world like Babylon, Ur, and Akhetaten, which were wonders of technology and wonders of religious iconography. I created the fictional city of Qabbat’lee, named after Qabbat, a father god and god of the sun, and imagined it as a place of political and religious significance–the City of Seven Gods–as well as a cosmopolitan center. I wanted to depict realistically the kinds of conflict that might emerge in such a place between people of different races, the nobility and the priesthood, and the nobility and her masses of peasant subjects.

As I began to write the story, I was drawn to themes of disillusionment and awakening, which may be taken as a more modern sensibility, though I believe those universal aspects of humanity had to exist in ancient times as well, and not just for the leisure class philosophers. We don’t know much about how common men like priests or laborers really viewed their world, and I wanted to explore that through this story.

So there’s the scoop behind the scenes. Let me know what you think if you pick up the book!