This was a tough one, which I submit with a heavy caveat.

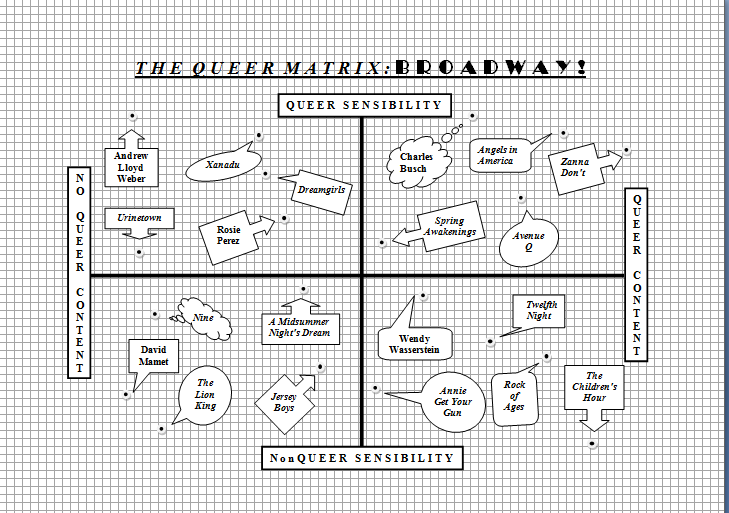

When it comes to theatre, musical theatre in particular, I think any work could be considered queer.

Beyond the clichés—gay men love show tunes, stage divas, and melodrama—what I mean to say is that it’s a medium in which performance can trump the playwright’s intention. A queer character can be played as villainous, heroic, insipid, wise, stereotypical or multi-textured, depending on the actor’s point of view. Queer subtext can be suppressed or inserted based on the director’s or the actors’ preferences.

The same choices are there for film or television screenplays, but I find there to be a greater degree of nuance and experimentation in theatre.

Theatre has also been a welcoming community for queer artists, all the way back to its creation in ancient Greece. Sophocles, one of the greatest Greek tragedians (e.g. Oedipus, Antigone, etc.), has been biographized as queer by historian Thomas Hubbard in Homosexuality in Greece and Rome. While queer themes were not commonly overt in the time period, we know of plays that told the stories of male/male relationships, including Sophocles’ intriguing title: “The Lovers of Achilles.”

Furthermore, theatre is a queer concept in itself: you can wear a mask and take on a completely different identity from your real life.

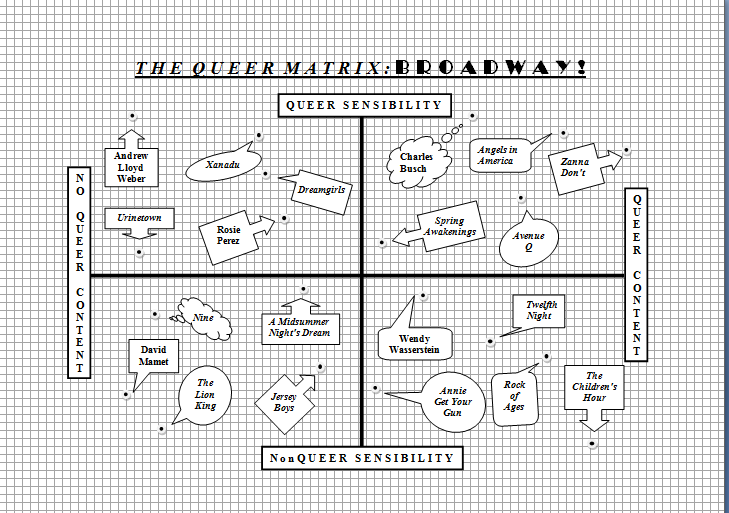

So, enough of taking myself too seriously, here’s what I came up with.

Per Jurgen, I put some thought into Shakespeare, a steady source of queer and non-queer literary debate, and picked out two plays which present queer themes in different ways.

Of course, there’s lots of cross-dressing in Shakespeare productions, and the steady device of a woman falling in love with another woman who is disguised as a man. The Merchant of Venice is one example.

Here, I chose Twelfth Night. But I put Twelfth Night in the Queer Content/NonQueer Sensibility quad because all the fun, experimental stuff gets sorted out in the end, with Viola marrying the Duke. Heteronormativity wins out again.

In contrast, I’ve always thought of A Midsummer Night’s Dream as queerly ambiguous, even though all the characters are in opposite-sex couplings. There’s Puck, the fey master of ceremonies, and a disintegration of social conventions—characters falling in love with people they shouldn’t. I couldn’t quite put it on the upper half of the Matrix due to Puck’s famous apologetic Act V speech:

“If we spirits have offended, think but this, and all is mended…”

But a lot has to do with the delivery, I think. Is he really sorry that he interfered with the young, starchy aristocrats’ lives?

andrewjpeterswrites.com goes dark next week while I’m attending Lambda Literary Foundation’s 2011 Writers Retreat for Emerging LGBT Voices!

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook