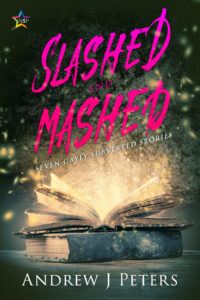

Today, my Pop Up Swap interview with Tom Cardamone continues, and we switch seats to discuss Slashed and Mashed…

TC: Andrew, I’m intrigued! Not many writers have more than one series under their belt before tackling short stories. The usual path is the reverse, so I’d like to hear about the steps that lead up to this project.

AP: I did start out as a writer in a typical fashion, submitting short stories to journals, but you’re right, I don’t have an extensive history with short fiction and anthologies, and I haven’t had a short story published in five plus years. I had pretty much stepped away from shorts in order to work on longer projects.

So the deal with Slashed and Mashed is I was writing content to create a Patreon page and thought it made a lot of sense to queer up some classic myths. That tends to be my fantasy métier, and I love gender-swapping and revisiting characters with a different spin.

So the deal with Slashed and Mashed is I was writing content to create a Patreon page and thought it made a lot of sense to queer up some classic myths. That tends to be my fantasy métier, and I love gender-swapping and revisiting characters with a different spin.

I ended up with a bunch of stories, and then I got more serious about them, running them by writing buddies and thinking about an anthology as a goal, whether I found a publisher or published the book myself.

I truly had no idea what my chances were getting anyone interested in publishing the collection. As you noted, I’m not known as a short story author, plus the kind of retold myths and fairytales that typically garner interest in the gay publishing world are happily-ever-after (HEA) romances, of which I had a few, but I didn’t want to limit myself to that.

So I pitched the idea to my editor Elizabetta at NineStar Press since she likes my writing and NineStar welcomes diverse fantasy and cross-genre titles, not solely focused on HEA romance and they do short story anthologies. We had a lot of back and forth about what would work best in terms of varying story length, mood, characters, and themes.

Not every piece I submitted made it into the collection. The publisher prefers “complete” stories, so the anthology leans toward longer works with start-to-finish plot arcs. I see the wisdom in that now that the book is out in the world. The fuller stories tend to get the most positive response from readers. Anyway, I’m happy with the variety in the seven pieces we included.

TC: How’d you arrive at the title?

AP: I also pitched a few possible titles to my editor, and we both liked Slashed and Mashed. I think it sums up the connective tissue. I wanted to reboot stories pretty boldly, and slashed is a nod to slash fiction, and I like that shorthand for subverting heterosexual canon.

TC: I loved the twist in the opening story, and not giving anything a way, I’m wondering if you’re a Mary Renault fan?

AP: Absolutely. I don’t read ancient world historical fiction as often these days, but there was a time when I was absorbed in it, and Mary Renault is the grand dame of ancient world historicals. I’m humbled you made that connection. With “Theseus and the Minotaur,” I wanted the story to have the feel of historical accuracy, fictional as it is. I wanted it to be a portrait of the two main characters with greater depth than the epic myth, which doesn’t really go beyond their surface characteristics and motivations.

TC: What was the first book of hers you read?

AP: Naturally, I started with The Persian Boy. I had big expectations, and that book was a case of meeting them and then some.

English/South African author Mary Renault. Image retrieved from Wikipedia

I’ve also read The King Must Die, The Last of the Wine, and The Charioteer. The Persian Boy remains my favorite. Renault is probably the most reliable historical storyteller in my estimation. I don’t know that for a fact, but she has such a voice and an ear and an eye for the time period, you just don’t question anything she says.

And her rendering of Alexander’s relationship with his slave Bagoas, as well as with his companion Hephaistion, feels so honest and real. They’re not heartwarming romances. I mean, there are definitely heartwarming moments, but they’re complicated as they necessarily would have been. Another thing that made me a Renault fan is the fact she took the story from Bagoas’s point-of-view, giving that lesser known historical figure the humanity he deserves.

TC: I’ve read some interesting discussions on-line about women writing gay stories, with the accusation that they’re crowding gay writers out of the market, though their audience seems to be women. I’m of the mind that this argument isn’t necessary but rather such books signify a cultural phenomenon that’s worth talking about. That said, some writers who happen to be women and happen to write gay characters are making fantastic books. Are there any that you’ve enjoyed?

AP: I haven’t been shy being one of the voices in that discussion, and I always qualify my position by saying writers should write whatever the hell they want within an ethical framework, and I admire many female authors who write gay characters.

My other lead-in is the issue of who gets to tell gay stories, I mean the ones that see the light of day, goes way beyond what women are or aren’t writing with regard to gay subjects. I think what a lot of people don’t understand about the #OwnVoices movement, which I’m proudly a part of, is it’s not an effort to elevate marginalized writers as “better” authors of marginalized stories. No one is winning that argument given the vicissitudes of what constitutes quality and value in literature. Issues like cultural appropriation and lived experience come up in the #OwnVoices discussion, but for me and a lot of authors I talk to, what’s even more important is equity, i.e. how do we support stories about marginalized communities written by marginalized writers?

The crowding out issue you mention is interesting and complex because you need to consider intersectionality and the fact that gay male white cis gender authors like myself face some obstacles in the industry on one hand but many privileges on the other that don’t exist for trans writers and queer writers of color and women writers in other contexts.

I’ve done some research on #OwnVoices in gay fantasy, and my conclusion that somewhere between five to 20 percent of published titles are authored by gay men sounds dismal at first blush. But then you step back and look at what’s getting published generally in queer/LGBT fantasy, and it’s a lot more white, cisgender G stories, and that’s regardless of authorship as far as I can tell. So really writers like me aren’t doing too bad in that regard and as allies should be talking about the lack of diversity within diversity so to speak.

I agree female-authored MM is a cultural phenomenon which has had a big impact on the market and perhaps more significantly, for some of us, on gay literature as a category and a tradition, which is slightly different from the idea of being crowded out.

I never describe my work as MM, for example, but that’s what publishers, reviewers and readers generally want to call it, and it’s gotten to the point where I see it as a generational thing. I run into young gay authors who talk about their work as MM. It was jarring to me at first. I mean, MM started as slash romance by women for women and intentionally tropish and eroticized, and none of these guys are actually writing that. But nowadays, you have folks calling books by André Aciman to Andrew Sean Greer to Adam Silvera “MM” so I think it’s a losing battle to be the grumpy older guy pointing out: hey, we used to just call books about gay people gay fiction. Though I still do that sometimes.

So setting aside my commentary, I’ve enjoyed many books with gay characters and themes written by female writers. Mary Renault probably shines the brightest for me. I was also blown away by Marguerite Yourcenar’s Memoirs of Hadrian, which similarly leaves you scratching your head: this couldn’t have been written in the twentieth century; it’s got to be translated source material.

In queer fantasy, I think Ellen Kushner’s Swordspoint is a classic, and Ginn Hale’s work stands out as well. I also loved Patricia Nell Warren’s The Front Runner, and now I think I’ve outed myself as partial to lesbian authors who take on the gay male subject.

TC: Back to Slashed and Mashed, with The Peach Boy, I was thrilled that not only did you visit my favorite literary landscape, Japan, but that you did such a believable job. I was transported. Can you tell us a little about the research that went into making this tale?

AP: Thanks! I’m glad. I know you’re a Japanese culture aficionado, and a ton more well-traveled and versed than me.

I looked fairly high and low for a story to subvert from Asian folklore. I actually tried doing something with my very favorite Chinese myth about how the panda got its spots, and then I gave some thought to “The Passion of the Cut Sleeve,” which is a surprising queer story from Chinese history about the relationship between Emperor Ai of Han and his court minister Dong Xian. Nothing worked in my head, and I couldn’t find any stories from Southeastern Asian sources that gelled for me either. Hopefully, I’ll have the chance to go back there and see if there’s something I can queer up.

Momotaro shrine in Aichi Inuyama, Japan. Photo retrieved from Wikipedia Commons

I have to say I was both excited and a little terrified by the prospect of taking on Japanese folklore. I adore Hayao Miyazaki’s animated films. They’re so imaginative and different from Western stories. I’ve also read and watched some gay manga (yaoi), and it’s really madcap and sentimental, which fascinates me. But it felt like quite a reach to successfully capture the voice and tone of that kind of Japanese lore.

I knew a little bit about Momotarō (aka the Peach Boy), and I started reading versions of the original legend. It’s strange in some ways, but I have to confess it’s also one of the more accessible Japanese hero legends for Western readers, so the lights started blinking in my head. I can do this!

I also read Royall Tyler’s Japanese Tales to get some background on folk beliefs and customs and settings. If you get the chance, take a look at “Two Buckets of Marital Bliss.” I think you’ll enjoy the humor there.

TC: I particularly liked that the story centered on an older gay married couple. What inspired you to spin it in this direction?

AP: I thought about taking the approach of queering Momotarō himself, but I discarded that pretty quickly because I already had two young adult hero pieces in the collection (“Theseus and the Minotaur” and “Károly, Who Kept a Secret”). What appealed to me more was reimagining the older, childless couple who find a boy inside a peach and focusing on what it would be like to be an older gay couple in 18th century Okayama Prefecture. More generally, I wanted to include multigenerational gay men’s stories in the collection.

Japan was still very much a feudal society in the 1700s, and that got me interested in taking the Momotarō story a bit deeper, how this older, peasant couple navigated taking in an orphan. And Japanese culture isn’t infected by the stridently homophobic religious beliefs of many other parts of the world, but I was aware there were and still are prejudices toward LGBTs based on traditional gender roles and norms. So I wanted to depict that part of the struggle, these two men, a widower and an older bachelor who made a home together in a small village and then face the decision of what to do with an orphaned child.

TC: While you supply some very needed positive portrayals of gay relationships and desire in Slashed and Mashed, you don’t sugar coat things. I was particularly glad to see a narcissistic gay character get his just deserts- were you following the form of fables or aiming for well-rounded characterization? And while much has been said about narcissism in the gay community, it’s always as an aside, and never dealt with head on- does “The Vain Prince” serve as something of a corrective?

AP: Well, I agree, but if I’m being honest it was not all that intentional of a commentary in “The Vain Prince.” The spoiled princess from “The Frog Prince” was my inspiration point, and I also had the contest of suitors from the opera Turandot on my brain. More so, I thought of that story as subversive in the sense that male beauty and certainly gayness aren’t things that get celebrated and indulged in traditional fairytales, so it struck me as time for a very pretty and very gay prince to have his day. Other than that, I think I held to form with a story about a cold-hearted beauty who gets a hard lesson in the importance of self-sacrifice.

Now I thought you might be leading into “Ma’aruf the Street Vendor,” who has the misfortune of falling in love with a young, handsome and very self-centered “artist cum model” Fareed. While the tone is light and absurd in that Arabian Nights reboot, I did think of their relationship as something that happens with some frequency in the gay community.

It’s kind of two thorns in one for me. You have this pretty, narcissistic guy who takes advantage of an older man he doesn’t really care about. Then you have this older guy who sacrifices everything because only a pretty young man makes him feel worthy and desirable. I think those are situations we still contend with in our community, and the beauty obsession has a negative impact on how we relate to one another. Part of Ma’aruf’s journey is recognizing he doesn’t need a hot, young guy to fulfill his sense of happiness, and in that I’ll admit I was channeling my criticism of youthful vanity as well as older guys who become fixed in the search for young beauty.

The other story that touches on the narcissistic theme is “The Jaguar of the Backward Glance.” I actually didn’t really think much about what I was doing with the gay characterization there until one of the story’s early readers, who happens to be straight, commented that the main character René is hard to like because he’s so petty after he gets discarded by his lover.

René’s story is set in the seventeenth century, and I had in mind both historical and contemporary challenges to gay identity formation. He’s this closeted thirty-five-year-old man, who is terrified of being discovered as gay and turned quite bitter toward the world because he can’t have what he desires. So when he finally experiences sex and affection then loses it because his lover falls back on heterosexual convention, it totally made sense for me that he’d be destroyed in the proportions of teenage heartbreak.

It’s frankly not so different from how I reacted to unrequited crushes as a young adult, and I hadn’t suffered nearly as many years feeling injured and alienated as poor René. He has suicidal and homicidal fantasies, which I can see as coming across as “petty” in relation to a failed week-long affair, but I felt gay readers could relate to that. René is a narcissistic character, but not so much by constitution as from the trauma of having to hide his gayness. I do think that’s the genesis of narcissism in some cases. We turn inward and create this inflated sense of ourselves as a defense against a hostile world.

TC: Can you talk about the global reach of the book? You have adapted tales from multiple cultures, was this your initial intent or did your reach grow as the project grew?

AP: I wrote a lot of classical myths initially in developing my Patreon page, and it hit me at some point I’d love to go broader with world folklore from the standpoint of representation as well as creating a collection that’s a little different from the ones that have come before. There are a lot of queer retold fairytale collections based on classic European sources, so part of my motivation was creating a collection that offered something new and different. For me, my natural tendency is to represent the community realistically, in all of its diversity.

TC: New York City pops up as a location, too. Our city is a character in much of literature. Sometimes I try hard to put a story somewhere else, other times I can’t wait to write what I consider a “New York story.” Were you of the same mind with your work here?

AP: In a way, yes. I’m one of the millions of gays who flocked to New York City as a place where I could be myself, and yes, I’ve read many gay novels set in NYC. Actually, I’d say those novels had a lot to do with me coming to NYC.

As a writer, I don’t think I’ve been as concerned about actively avoiding NYC as a locale versus being part of that breed that’s terrible about choosing to write what I know. I tend to write stories in fantasy or historical settings. Then, even with my contemporary work – the Werecat series and Irresistible – the stories came to me as starting in New York City, but then I had the characters running off to far flung places that served the plot.

I will say when I get the chance to place situations in the city where I live, it’s a big weight off my shoulders. Zero location research went into “A Rabbit Grows in Brooklyn.” Well okay, I did peek at a street map of Fort Greene, on which I based Ramon’s neighborhood. Ma’aruf’s story also begins in New York City, Queens even, where I live, so that setting was easy for me to render.

TC: In our chat about my short story collection, Night Sweats: Tales of Homosexual Wonder and Woe, you brought up a favorite, out-of-print gay classic, Saul’s Book by Paul Rogers. In your research for Slashed and Mashed, did you uncover any gay titles that deserve some renewed attention?

AP: I mention in my author’s note, there are two gay fairytale collections that inspired me to try my hand at short retellings: Jeremy McAteer’s Fairytales for Gay Guys and Lawrence Schimel’s The Drag Queen of Elfland. Somehow, I bet you’re familiar with the latter, Tom. Some of Schimel’s pieces remind me a bit of yours in subject and mood. Schimel also explores HIV+ characters in his stories, which I think is rare and so important for a modern fairytale collection.

TC: Cool talking books and stories with Andrew, thanks for this, I hope we get a chance to do it again!