Banner from East Branch of Dayton Metro Public Library System, labeled as public domain

It’s the American Library Association’s annual Banned Books Week, September 24th through 30th, and I often do a post here in support of the cause.

From ALA’s website:

“Banned Books Week is an annual event celebrating the freedom to read. Banned Books Week brings together the entire book community — librarians, booksellers, publishers, journalists, teachers, and readers — in shared support of the freedom to seek and express ideas, even those some consider unorthodox or unpopular.”

The United States has an unfortunate history of book burnings and other efforts to ban and censor books that present ‘controversial’ topics, often defined as such by religious institutions. According to the ALA, one of the top reasons for books being challenged – requested to be removed – in library systems is the portrayal of sexuality, particularly in childrens and young adult books that contain LGBT characters.

For example, the top ten challenged books of 2016 include five books with LGBT content, including two books about transgender kids (I Am Jazz by Jazz Jennings and George by Alex Gino).

Here’s a cool video that shows all ten of those books:

Access to LGBT books has both personal and political significance to me. As a young reader, in my late teens, I pretty much desperately searched for books to help me understand my attraction to other guys. I wondered if there was something wrong with me, if it was even possible to live my life as gay. I knew no one who was gay. The little bit I knew about gay people was from overheard jokes, based on stereotypes. Gay men were effeminate, buffoons. And I caught some information from the news, which occasionally covered the AIDS epidemic, a frightening image of what it meant to be gay.

I wasn’t out, and I certainly wasn’t courageous enough to ask a librarian to point me in the right direction. So I quietly and surrepticiously searched the libary catalogue system for words like “homosexuality” and “gay.” In those days, LGBT books tended to be shelved in discreet, back or upper level areas of the stacks. It might have helped on one hand for the books I was looking for to be more visible, to help me understand that I had nothing to be ashamed about. Though at the time, it was helpful for me to be able to sneak into a desolate area of the library, grab a book, hide myself in a cubby, and read without anyone knowing what I was reading. In college, I got a little bolder and actually took some of those books out of the library, though I kept them hidden in my bedroom.

That was back in the late 1980s, and the books I found were either clinical books that were fairly equivocal about the nature of homosexuality – a perversion or a natural place on the spectrum of homosexuality – or they were gritty books about gay subculture and the sex trade (books by William S. Burroughs and Paul T. Rogers’ Saul’s Book, which have been banned or challenged over the years). In most ways, they were pretty far aloft of my experience of myself and the world, but they showed that gay people existed, a fairly mind-blowing discovery for a younger me, and comforting. If I hadn’t found those books, I don’t think I would have shaken off the anxiety and depression that was killing me. A few years later, I embarked on living an honest life as a gay man.

Nowadays, it’s gratifying to see many libraries acquiring a diverse collection of LGBT books, from childrens, young adult, adult fiction and nonfiction, and a variety of genres. I don’t mean to denigrate William Burroughs, but it’s pretty nice that young LGBTs aren’t limited to his body of work as a sole point of reference! And libraries now have LGBT books mixed in with their popular collections and childrens/young adult collections. Some of them even create displays for Pride Month and National Coming Out Day.

From talking to LGBT kids, which was my principal métier as a social worker, I can attest to the fact that many young people can access LGBT-themed books more easily today. They’re coming out younger, with greater confidence and with family support, and some describe LGBT literature as fairly normalized in their schools and libraries, and/or are comfortable with advocating for better representation of LGBTs. Some have parents who take the lead in that regard, and not infrequently, when I meet new acquaintances, readers and other writers, they ask me where to find my books because they have a son or niece or a neighbor’s kid who is gay.

Still, there are some LGBTs who have described their experiences as similar to my own — wanting to read books with characters like themselves but needing to do so privately because they’re not quite comfortable being “out.” And, particularly in socially-conservative rural and suburban areas, it’s not so easy for them to find LGBT books.

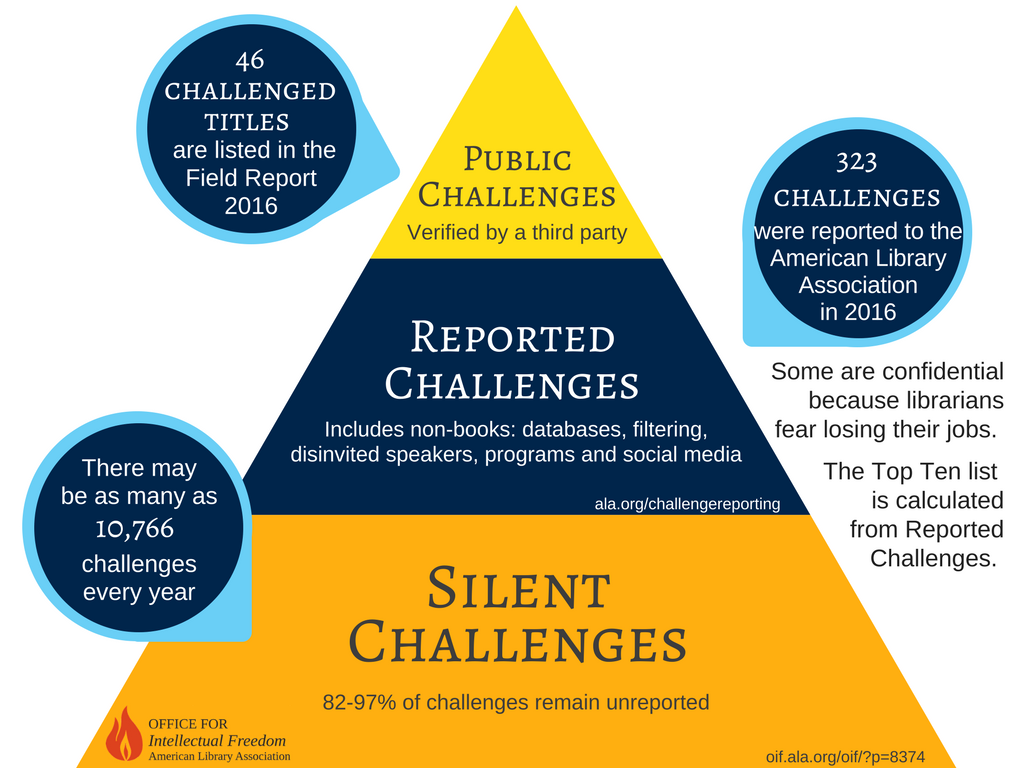

That’s why Banned Books Week remains necessary. It reminds us that the progress we have made is both fragile and not fully realized when you look across the country, and wider across the globe. As recently as last year, This One Summer by Mariko Tamaki, a young adult graphic novel with LGBT characters, was removed from libraries in Minnesota and Florida through challenges. The ALA Office of Intellectual Freedom tracks book challenges and finds that 10% of them lead to the removal of a book. That might not sound like a lot, but in each community where censorship occurs, it affects many thousands of people, in addition to perpetuating the view that portrayals of sexuality, particularly LGBTs, are unnatural and unsafe for young people.

You can support the freedom to read by raising awareness of Banned Books Week, and books that are targeted themselves. Here’s a handy resource page from ALA and an infographic that shows the scope of the problem:

Great article Andy. It’s nice to see things are changing for the better!

Hey January – Thanks for reading and dropping a comment. Yeah, there’s a huge difference in how libraries handle LGBT content these days, with many seeking it out to diversify their collection versus turning it away, which was true when I was growing up.