October 11th, 2016. It’s National Coming Out Day (NCOD), and here’s a little history. According to the Human Rights Campaign, NCOD was first celebrated in 1988 on the anniversary of the 1987 March on Washington for Lesbian and Gay Rights. Gay-affirmative psychologist Rob Eichberg and activist leader Jean O’Leary are credited with creating NCOD, and Keith Haring donated his artwork (above) as the logo. The purpose is for LGBTs to share their stories and thereby raise awareness and visibility.

I was not dancing out of the closet in 1988. I was a college freshman and only slightly aware that my stubborn, unrealized attraction to guys, which I was trying to suppress, meant that I was gay. I had had crushes on guys going back to elementary school, though I wouldn’t have described them as such at the time. In some ways I didn’t have the reference points to understand what I was going through. People in my world rarely talked about the possibility of boys liking boys, and when they did, they talked about it in a way that scared the hell out of me.

In high school, I became more aware of the existence of gay people, though mostly as an abstraction. I saw frightening images of gay men dying of AIDS in the media, and that was happening in big cities like New York and San Francisco as far as the national news was concerned. I was in suburban, upstate New York. No one declared that he was gay in my high school, and the few guys who fit the stereotype were the butt of jokes and shoved around the hallways at school. I was never a bully, but I laughed along at fag jokes and distanced myself from anyone rumored to be gay.

If that was what being gay was, I did not want to be that. I made a pact with myself that I would not be that, never, ever, no matter what I had to do.

I’ve come to understand that’s a bargain a lot of LGBT people make. Though, funny, as determined as I was mentally to not come out, my body and I might say some better sense I didn’t even know I possessed was more powerful. It was sort of like a spiritual experience, or as close to that as I can imagine, being an atheist. I do believe that something truer than I was, something stronger than I could consciously be, led me out of the closet and probably saved my life.

That’s certainly not to say it was all joyous and affirming at first. My journey out of the closet began with a crushing sense of loneliness and panic attacks that strangely didn’t seem to have any particular trigger. I’d feel like I was having a heart attack in the middle of class, and sometimes that chest-constricted, dizzy, breathless feeling just happened when I was alone in bed at night. I went to doctors, and medical tests showed there was nothing wrong with me, even though clearly this wasn’t normal. My body was rebelling against me, and in retrospect, I came to understand that it was demanding that I deal with part of my nature I was trying to banish.

I picked out a psychologist from a referral book at the college counseling center, quietly drawn to a group of words in her list of specializations: “male identity issues.” Deciding on a therapist based on that bit of info was not much more discerning than flipping through the book and landing on a page, but boy was I lucky. I think she understood what I was going through as soon as I walked through the door. Over a year of sometimes confrontational techniques, she helped me understand that my gayness was nothing to be ashamed of.

I remember leaving her office one day, and saying the words out loud: “I’m gay.” In that moment, the world was unveiled, and it was bright and colorful and full of possibilities, and I realized what it was like to walk down the street without my eyes pointed at the ground, and yes I felt incredibly free. Of course, it wasn’t always so easy coming out, but making that connection–that my loneliness and panic stemmed from suppressing my sexuality–it was like finally getting a diagnosis and a cure for a mysterious and debilitating disease.

As a side note, I should mention another thing that helped me tremendously was Rob Eichberg’s Coming Out: An Act of Love, which my psychologist recommended that I read.

I place myself among gay men in that in-between Gen X cohort, who came of age in the post-sexual revolution/AIDS-phobic 1980s and before the kinder new millenium with LGBTs on primetime, Gay-Straight Alliances in high schools, and marriage equality. Certainly there’s variation, but I think that many of us followed a trajectory of keeping our gayness hidden in high school and coming out when we were “out of the house,” whether going away to college or moving away from our families. It makes me happy to hear young people say: “I was never not out.” I’ve worked in private practice with older men who came out in their 50s, after marriages and raising kids.

Is one path harder or easier than the other? I don’t know. On one hand, coming out older brings to bear regret and often relationships to repair. On the other hand, coming out young sometimes puts kids in situations like bullying and rejection, which they’re not yet emotionally equipped to handle.

As I reflect on my coming out journey and those of younger people and older people I’ve known, a common thread is joy. That moment of knowing yourself, feeling free to be yourself, well, it may sound cliché, but it’s a gift that we get as LGBT people. And that’s worth celebrating for sure.

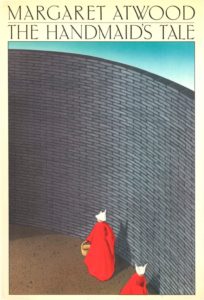

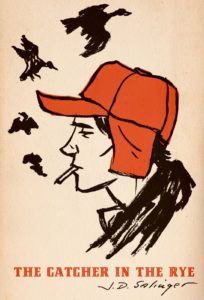

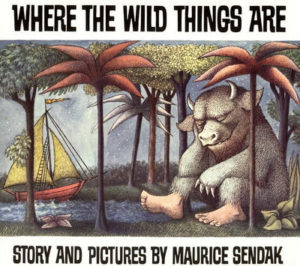

Banned for: excess vulgar language, sexual scenes, things concerning moral issues, excessive violence and anything dealing with the occult.

Banned for: excess vulgar language, sexual scenes, things concerning moral issues, excessive violence and anything dealing with the occult.

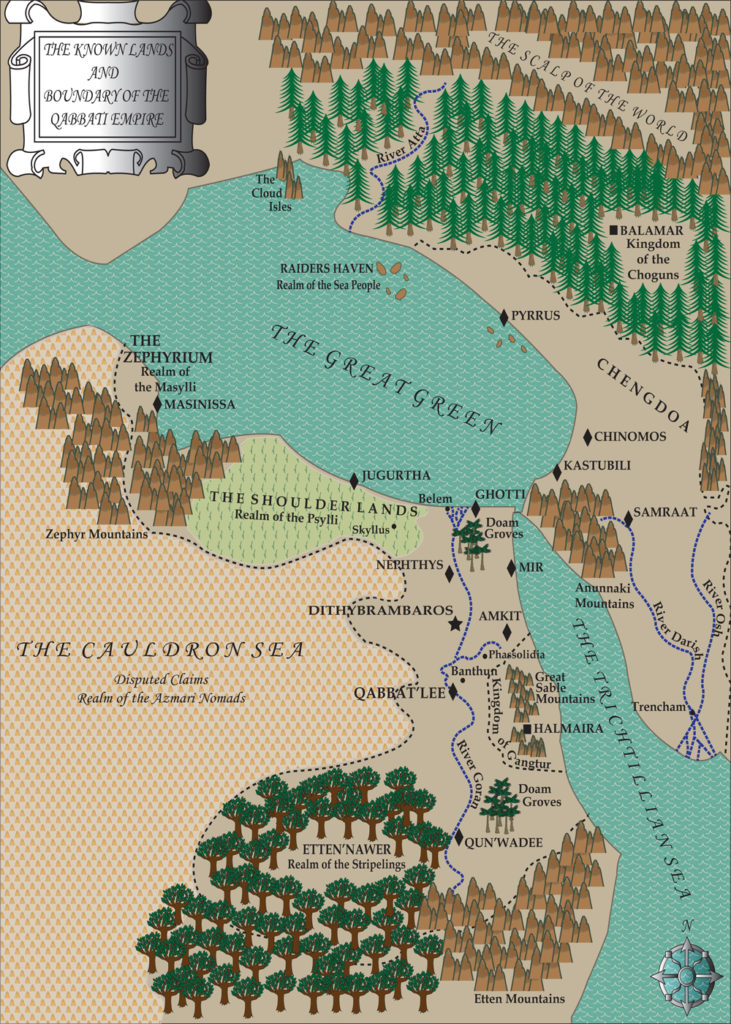

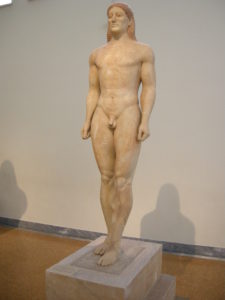

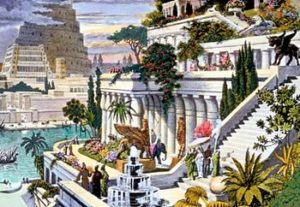

Praxtor held out the golden tulip. “For you, Kelemun. In tribute to the most handsome man in all of Qabbat’lee.” He turned to the court and raised his voice. “The most handsome man in all of the emperor’s lands.”

Praxtor held out the golden tulip. “For you, Kelemun. In tribute to the most handsome man in all of Qabbat’lee.” He turned to the court and raised his voice. “The most handsome man in all of the emperor’s lands.”